In a new California case study, NASA-led researchers highlight how modest vertical land motion can significantly impact local sea levels in the future.

Amounting to just fractions of inches per year — the slight change can increase or decrease local flood risk, wave exposure and saltwater intrusion.

By 2050, sea levels in California are expected to increase between 6 and 14.5 inches (15 and 37 centimeters) higher than year 2000 levels, according to the government agency.

Melting glaciers and ice sheets and warm ocean waters are mainly to blame.

“In many parts of the world, like the reclaimed ground beneath San Francisco, the land is moving down faster than the sea itself is going up,” said lead author Marin Govorcin, a remote sensing scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

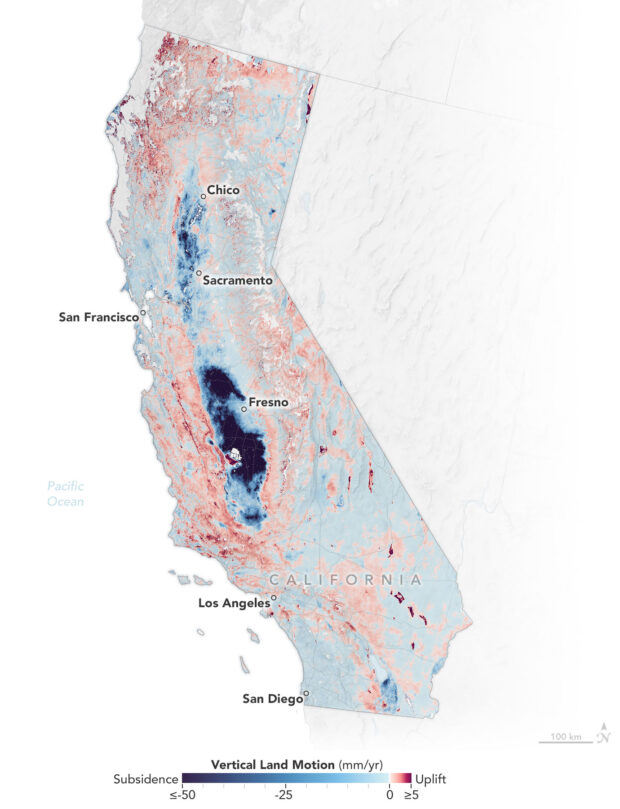

The new study illustrates how vertical land motion can be unpredictable in scale and speed; it results from both human-caused factors such as groundwater pumping and wastewater injection, as well as from natural ones like tectonic activity.

Direct satellite observations can improve estimates of vertical land motion and relative sea level rise, the researchers said. Current models based on tide gauge measurements cannot cover every location nor all of the dynamic land motion at work within a given region.

Researchers analyzed radar measurements made by ESA’s (the European Space Agency’s) Sentinel-1 satellites and motion velocity data from ground-based receiving stations in the Global Navigation Satellite System.

They then compared multiple observations of the same locations made between 2015 to 2023 using a processing technique called interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR).

The team found the land in the San Francisco Bay Area — specifically, San Rafael, Corte Madera, Foster City, and Bay Farm Island — subsiding at a steady rate of more than 0.4 inches (10 millimeters) per year mainly due to sediment compaction.

Accounting for this subsidence in the lowest-lying parts of these areas, local sea levels could rise more than 17 inches (45 centimeters) by 2050, more than double the regional estimate of 7.4 inches (19 centimeters) based solely on tide gauge projections, the researchers said.

Not all coastal areas in California are sinking.

The researchers mapped uplift hot spots of several millimeters per year in the Santa Barbara groundwater basin, which has been steadily replenishing since 2018.

They also observed uplift in Long Beach, where fluid extraction and injection occur with oil and gas production.

In the middle of California, in the fast-sinking parts of the Central Valley (subsiding as much as 8 inches, or 20 centimeters, per year), land motion is influenced by groundwater withdrawal.

Periods of drought and precipitation can alternately draw down or inflate underground aquifers, the team said.

These fluctuations were also observed over aquifers in Santa Clara in the San Francisco Bay Area, Santa Ana in Orange County, and Chula Vista in San Diego County.

Along rugged coastal terrain like the Big Sur mountains below San Francisco and Palos Verdes Peninsula in Los Angeles, the team pinpointed local zones of downward motion associated with slow-moving landslides.

In Northern California they also found sinking trends at marshlands and lagoons around San Francisco and Monterey bays, and in Sonoma County’s Russian River estuary. Erosion in likely played a key factor, researchers said.

Scientists, decision-makers and the public can monitor changes via the JPL-led OPERA (Observational Products for End-Users from Remote Sensing Analysis) project. The OPERA project details land surface elevational changes across North America, shedding light on dynamic processes including subsidence, tectonics and landslides.

(Original article written by Sally Younger NASA’s Earth Science News Team)

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality  How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll

How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll  Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs

Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs  Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk