CoreLogic announced a preliminary range of insured loss estimates for the Eaton and Palisades Fires in Los Angeles, Calif., of $35 to $45 billion, but there are a lot of factors that could change the numbers.

“We don’t know,” Tom Larsen, senior director of insurance solutions, repeated multiple times during a webinar yesterday, referring to uncertainties about factors like smoke damage beyond any historical reference point, the prevalence of minimally insured and uninsured homes, and even potential mudslides that may occur years down the road.

Before reviewing these in some detail, Larsen explained that CoreLogic produces its estimates from the ground up, starting at the parcel level—looking at the building characteristics of properties in the impacted areas, such as square footage and age, and eventually using reconstruction valuation models to estimate costs.

The next step involves looking at aerial imagery, further annotating the extent of damage to properties, and also relying on the judgment of CoreLogic experts “on the ground, who are looking at claims data, looking at what are the [cost] patterns from the past.”

“There’s a significant amount of uncertainty,” he said. One key reason: The fires are still burning.

Indeed, moderator Jon Schneyer, director of product and content, noted that as of Thursday, Jan. 16, when the CoreLogic estimates were announced, the Palisades fire was roughly 22 percent contained, and the Eaton fire was 55 percent contained.

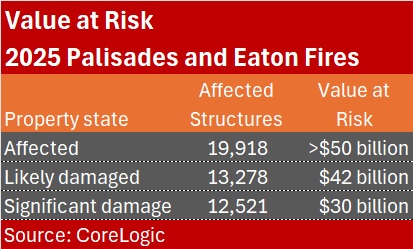

CoreLogic has counted more than 19,000 structures in the affected areas for the two biggest 2025 fires. “The smoke cloud was there, there was a lot of heat, but we’re not quite sure [if there] was … much damage,” Larsen said. He noted that there is more than $50 billion of exposure associated with the 19,918 structures, and that CoreLogic winnowed down the totals into two buckets: likely damaged and significant damage.

Values associated with the structures with “likely damage”—some charring on the outside of the house and some smoke damage—total $42 billion.

There’s more certainty about structures with “significant damage”—around 12,500 of them, which CoreLogic values at $30 billion.

On the basis of these figures, CoreLogic ended up with the $35-$45 billion range for both commercial and residential losses—primarily residential—with about two-thirds of losses attributable to the Palisades loss.

While CoreLogic promises to provide final insured loss estimates once the fires have been fully contained, there are a lot of unknowns right now, some of which will persist for a while.

“Smoke damage is a really important unknown…We haven’t seen a really large, extensive urban fire [before, where the] smoke perimeter was much larger than the fire perimeter,” he said. Smoke damage mitigation may be costly, but insurance terms and conditions are unclear, he suggested. “We’re really not sure. We’re going into a new area where we haven’t seen a lot of historic data yet,” he said.

ITV is another uncertain component in loss estimation, he said. “We’re trying to use our own best estimate of the values and not the values that any insurer or the homeowner might have,” he reported.

Another complication: the ongoing insurance crisis in California. Affordability and availability issues have pushed some homeowners into the FAIR plan, while others choose the minimal coverage of a dwelling fire policy to satisfy mortgage requirements.

“That could reduce the insured losses, but the data is not there to support any really firm determinations at this point in time. The data is always a year in arrears and very aggregated,” he said. Larsen also noted that while disaster cost estimates usually involve a low total of uninsured homes, with prices going up, more Californian’s could have opted out of buying coverage at all.

“We don’t know,” Larsen said.

Later, he noted the prospect of post-fire flood destabilizing the land—and potentially lengthening the timeline for reported claims. He gave the example of the 2017 Thomas Fire in Santa Barbara and floods occurring the next winter (the Montecito floods) that damaged many homes.

“The determination was that the cause of that flood was the prior fire, which meant that the landslide and flood were not covered by flood insurance—an optional coverage that most people don’t have—but was instead part of the fire policy. The causation was this fire. So, for this hilly mountainous area, in both the Eaton fire and the Palisades fires, there is the potential for landslides in the next few winters.”

“We don’t know and we will find out,” he said.

Referring to a more obvious factor causing post-event time lags for recovery and costs—demand surge—Larsen noted, “There are going to be a lot of inefficiencies and wait times for getting plans approved, getting buildings permitted and inspected. All those will be contributing to a higher-than-average reconstruction cost.”

How long will it take before rebuilding starts in the Los Angeles area?

Schneyer directed the question to Garret Gray, president of CoreLogic Insurance Solutions, whose own home has smoke damage from the recent fires.

“It’s a question that we’re all grappling with—just even when are we going to get access?” Gray said. “My house is still standing, but I can’t even get within a couple miles of my house. And I’m hearing all sorts of estimates on when I will be able to” do so. None are shorter than 30 days from now, he said, noting that the “somewhat reputable sources” of the disparate time estimates include HOA boards and Palisades community officials.

Gridlock and Panic

Gray was the first CoreLogic representative to talk about the damage associated with the wildfires during the webinar—not giving the usual description of how events and losses are modeled, but instead sharing his own harrowing personal experience of evacuating from an area in flames.

“It shakes me every time I tell it,” Gray said, recounting the details of his day on Jan. 7, when he received frantic texts from his children’s school about an evacuation in progress. “As I got closer, the gridlock and the panic got a bit stronger as people were trying to both get to their kids and then try to get out of the area,” he said, recalling his drive toward the school. “A lot of people ended up abandoning their cars and running. If you go through the area, you see multiple cars that were just consumed by fire in the aftermath,” he said.

In recent days, Gray was able to access the area once. Returning to a path on which he and his children ran toward each other when they were finally able to connect, Gray reported that every house on that path has been completely lost to fire.

Mitigation Works

Gray’s own home located a half-mile away, however, is still standing. He doesn’t attribute that entirely to luck, but also to some things he learned through CoreLogic’s fire science team, which prompted mitigation efforts. In particular, he pointed to the removal of two large oak trees that were close to the house.

In the aftermath of the fires, some smaller remaining trees near the house were singed all the way down. Pool equipment melted completely, and the patio furniture has ash and burn marks, he noted, showing aerial photos (from Vexcel Group). “It’s very clear to me that if that [oak] tree was still existing, that would most likely have ignited. And then, it’s so close to the house that the house would probably have not been able to survive that.”

“So, mitigation efforts work. [It] doesn’t mean it worked for everybody down the path of the fire because the fire just got so intense and ran so hot and fast… It’s not that mitigation efforts will always work. But I think in this case it did,” he said.

Extreme Conditions

Two other speakers during the webinar—Jamie Knippen, product manager of CoreLogic’s Wildfire Solutions, and Dr. Tom Jeffery, CoreLogic’s chief wildfire scientist—gave more detached views of the way in which wildfires spread to become conflagrations, the combination of extreme conditions that made these particular fires so strong and hard to battle, and the factors that cause some properties to burn to the ground while others survive.

Knippen, who showed before-and-after photos of a neighborhood destroyed by the Palisades conflagration, noted that many homes were situated 10 feet or less distance from neighboring homes, “which allowed for the fire to jump from structure to structure. And due to the high winds, there was little that could be done to stop it,” she said.

Defining a conflagration as “a wildfire that begins in a natural vegetation environment and then transitions into an uncontrollable structure-to-structure fire in the built environment,” Knippen said a key takeaway from the images “is that the structures themselves became the primary fuel…”

“It brings further awareness of how fuel always isn’t just vegetation. The fuel that can drive a fire can be vegetation alone, a combination of vegetation and structure, or solely the structures themselves, which raises new questions,” she said.

Jeffery, who described the usual conditions for wildfires—winds and dryness—reported that the extreme conditions surrounding the recent fires made them uncontrollable. Wind is not an uncommon occurrence in a wildfire, he said. “You may have 10-mile-an-hour winds, 20-mile-an-hour winds. Here, [there were] 30 to 50 [mph] sustained winds…When you get above that, you’re into hurricane-force winds,” he said, noting that extreme gusts surpassed 100 mph.

It is also uncommon for all the weather conditions associated with wildfire activity to be piled on top of one another. “You have sustained winds of 30-plus miles an hour… You have relative humidity that is less than 10 percent, drought conditions and temperatures above 70 degrees. We’ve met all those criteria. We just have never met them all in the United States. We’ve never met all four of those factors in January. This is the first time that we’ve ever seen that,” he said.

“That is reason for concern because it really means this is out of cycle. It’s not occurring at the time where it should normally occur,” he said, later going on to talk about the fact that multiple fires burning—even smaller ones that had to be dealt with to prevent them from spreading—taxed fire-suppression resources.

Among other problems, the high winds hampered the use of aircraft, leaving ground crews to combat intense fires and deal with the rapid spread via wind-blown embers—not just small ones, but burning limbs broken from trees by the wind gusts.

In a conflagration, there will be multiple structures burning simultaneously, “and it’s not just two or three…not just 10 or 12. You could have a hundred or more homes all on fire in one neighborhood at the same time. Not only is that an intense fire, it’s also generating heat, it’s generating flames, and most importantly, it’s generating those embers…You’re fighting the fire that exists, and the embers mean that you have to proactively look to where the next fire is going to start when those embers fall out of the sky and either ignite another structure or more area.”

Earnings Wrap: With AI-First Mindset, ‘Sky Is the Limit’ at The Hartford

Earnings Wrap: With AI-First Mindset, ‘Sky Is the Limit’ at The Hartford  20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut

20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut  Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk  RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit

RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit