Phoenix has become a nerve-wracking bellwether for extreme heat. Arizona’s capital recently endured a three-week stretch when every day broke a heat record, with thermometers peaking at 117F (47C) on Sept. 28.

Yet even below the threshold of smashing records, Arizona is also “having hotter days more often, that last a little bit longer,” noted Erinanne Saffell, the state climatologist. Chronic heat at this scale poses its own dangers, without generating nearly as much attention as record-setting extremes. And there have been 92 days in Phoenix this year that were hotter than 95F but didn’t breach 110F.

It’s not just Phoenix experiencing more days that are merely very hot. Tampa, Florida, has seen 132 days this year hit 90F or higher, and Raleigh, North Carolina has notched 111 days above 85F. Much of the US has experienced a “zombie summer,” with abnormally high temperatures that meteorologists expect to last through the end of October.

Sustained bouts of below-record heat have health and economic impacts, although researchers say they’re still under-studied. “Chronic heat doesn’t get the attention it needs,” said Matt Brearley, an expert in heat physiology who conducts research and has advised Australian emergency responders, industrial workers and athletes, including Olympians. “It’s not as sexy. It doesn’t get headlines.”

During the most severe heat waves, people are told to avoid prolonged time outdoors, stay cool, hydrate and be on alert for the symptoms of heat illness, such as headache, nausea and confusion. But less unusual levels of heat can also have cumulative effects that are hard on the body.

Read More: How Extreme Heat Is Reshaping Daily Life

“We don’t have a great deal of solid evidence about the physiological tolerance for multiple days — if not weeks or months — of extended exposure to this heat,” acknowledged Vivek Shandas, a Portland State University expert on climate change and cities. But he described chronic heat as a kind of “death by 1,000 cuts.”

Bodies need to shed heat. When hours or days tick by and they can’t, the heart pumps harder. Metabolism speeds up, straining the cardiovascular system and potentially raising the odds of a heart attack or stroke. Blood flows toward the skin and away from critical organs, leading intestines to leak toxins the body’s trying to get rid of. Dehydration left untreated long enough can strain the kidneys, sometimes to failure.

Whether people respond differently to, say, a week or more of 95F days, compared with two 105F days in a row, is a question without much research attention to date, Shandas said.

Shandas is proposing a new way to measure potentially harmful heat exposure, in units of “degree-hours.” Having a common metric would allow people and communities to discover thresholds when cumulative exposure to persistent, non-record-breaking heat begins to affect health.

“We’re trying to bring the ‘duration’ conversation in a bit more centrally,” he said. “Because right now, it’s all about how hot it gets.”

As rising temperatures, including steadily higher highs, become a greater focus for climate scientists, public health experts, emergency personnel and others, the United Nations has distinguished between extreme heat spikes and “slow onset” rising temperatures, both of which incur losses to the economy and society.

Read More: When Hot Weather Arrives, Worker Productivity Is at Risk

Saffell said that in Arizona, chronic heat shows up most significantly at night, when people physiologically need a break from the heat. Temperatures in Phoenix stayed above 90F for 39 nights this year.

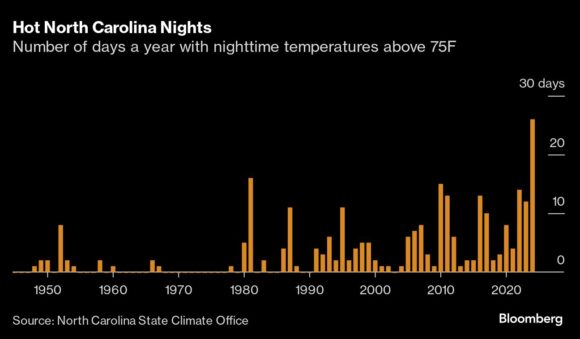

The same is true in places not known for “blockbuster heat,” a phrase used by Kathie Dello, North Carolina’s state climatologist. The state’s heat is “not always record, but it’s relentless,” she said.

“Nighttime temperatures are so shockingly different” from what they were a generation ago, Dello said, that a chart showing the change “is truly the graph you can put in front of people and say, ‘Here’s a climate impact.'”

Shandas is conducting research into how cities cool at night, block by block, building by building, and says there’s still a need for better data.

He’s seen projects pull in neighborhood-level heat data from more than 100 cities, but only for morning, afternoon and evening hours. “We haven’t done it in the middle of the night, partly because we can’t get volunteers to stay up,” he said. He is hoping to learn why some areas heat up or cool down faster than others.

Outdoor workers who have little or no home cooling may be particularly at risk from rising nighttime temperatures, said Brenda Jacklitsch, a health research scientist at US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Workers need time to acclimatize to hot conditions, whether they’re new on the job or just coming back from a week or two of vacation somewhere cooler. Failure to let people adjust to higher temperatures when starting a job or returning to one may be the leading factor in heat-related workplace deaths.

Singapore last year issued guidelines for outdoor work keyed into specific conditions, from an above-average to a rare “wet bulb globe temperature” — a measurement that combines heat, humidity, wind and sunniness. For example, at a wet bulb globe temperature of 31C (about 88F), employers must give workers “adequate” rest under shade; at 32C, they must provide rest breaks of at least 10 minutes an hour for workers doing hard physical labor. And at 33C, they must stretch the breaks to 15 minutes, ensure workers hydrate hourly and establish an emergency response plan.

Shandas says that there needs to be more consistent communication from authorities to the public throughout heat season, not only in emergencies: “The emergency response doesn’t have the capacity to reach everybody around the region with a longer, sustained chronic heat.”

As a consequence of its rising temperatures, both average and extreme, Arizona cities are also leading experiments on how to address it. Tucson in June adopted a heat action plan and a worker-protection ordinance that is comprehensive in scope because it addresses both ways to prevent heat risk at all levels and ways to manage it when necessary, according to Sara Meerow, an expert in urban resilience at Arizona State University.

“We need to be thinking, not about heat waves and heat as a short-term disaster, but actually as a heat season,” she said.

Top Photo: Construction workers in Folsom, California, US, on Wednesday, July 3, 2024. California’s biggest power utility had warned of the potential outages as the state faces a period of high wildfire risk as power demand surges to keep air conditioners running with temperatures in Sacramento remaining above 110F for daytime highs this week, National Weather Service computer models show. Photographer: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg

How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll

How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll  RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit

RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit  Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb

Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb  20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut

20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut