More than 20,000 motorcyclists who died in crashes in the U.S. since the mid-1970s would have survived if stronger helmet laws had been in place, according to a newly released study from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

If every state had helmet requirement laws in place between 1976 to 2022, a total of 22,058 motorcyclists’ lives could have been saved, the data showed. The number represents 11 percent of all rider fatalities during that time span.

“Requiring all riders to wear helmets is a commonsense rule not that different from requiring people in cars to buckle up,” said IIHS President David Harkey. “We have an obligation to protect everyone on our roadways through smart policy.”

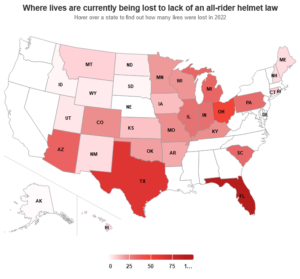

Just 17 states and the District of Columbia have all-rider helmet laws in place.

More than 6,000 motorcyclists were killed each year in 2021 and 2022, the most recent years with available statistics.

The study found that if the rest of the states required helmets, the death toll could be cut by as much as 10 percent.

Other measures like crash prevention technology that’s better at detecting motorcycles and mandatory antilock brakes on motorcycles themselves are also needed to improve rider safety, the IIHS said.

“Wearing a helmet is one of the biggest things riders can do to protect themselves from death and traumatic brain injury,” said Eric Teoh, IIHS director of statistical services and the author of the paper. “We understand that requiring helmets for all riders everywhere would be unpopular with some motorcyclists, but this could save hundreds of lives each year. Those aren’t just numbers. They’re friends, parents and children.”

The first all-rider helmet laws took effect in 1967, after the National Highway Safety Act made them a prerequisite for certain highway safety and construction funds. By July 1975, 47 states and the District of Columbia had such laws on the books.

In the years since the funding restriction was removed in 1976, most states have weakened their helmet laws to be applicable only to riders under 18 or 21 years old or repealed them altogether. A trend that has persisted even as seatbelt laws have become more stringent, the IIHS noted.

To determine the human cost of allowing unhelmeted motorcycling, Teoh compared the number of helmeted and unhelmeted riders killed each year in jurisdictions with and without all-rider helmet laws, allowing him to estimate helmet use rates for the states when all-rider laws were in effect and when they weren’t. He then estimated the number of lives that would have been saved each year if all-rider helmet laws had been universal throughout the entire 1976-2022 period. For that calculation, he used the 37 percent decrease in motorcyclist fatality risk associated with wearing a helmet established by other published research.

In another analysis, he estimated the cumulative effect of allowing unhelmeted motorcycling within each state.

Population-level helmet use has increased over time in jurisdictions with and without all-rider helmet laws.

Helmet use rates in states with all-rider laws were generally 2-3 times as high as in states without them over the study period. Teoh’s estimates take those historical changes and differing helmet use rates into account.

The number of lives lost as the result of laws that allow unhelmeted riding ranged from 182 in 1976 to 673 in 2021. Most states had all-rider laws in 1976, but compliance was spotty, the study found. Helmet use was higher in 2021, but far fewer jurisdictions required them.

By state, the largest number of lives lost — 2,536 — was in California, primarily due to its large population and long riding season. Further excess deaths have been averted in that state since 1992, when an all-rider helmet law went into effect there.

Other states that allow unhelmeted riding with high numbers of additional deaths include Texas (2,490), Florida (1,786), Illinois (1,738), Ohio (1,651), Indiana (1,151) and South Carolina (1,000).

“Requiring every rider to wear a helmet is a simple change that could have a dramatic and immediate effect on fatality rates,” Harkey said. “With 6,000 riders dying every year, it’s unconscionable that we haven’t already made these laws universal.”

Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages

Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages  Chubb CEO Greenberg on Personal Insurance Affordability and Data Centers

Chubb CEO Greenberg on Personal Insurance Affordability and Data Centers  Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality  Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash

Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash