Rick Wilmer spends most of his work days at the office. But every so often, the chief executive officer of ChargePoint Holdings Inc. will make his way to the company’s laboratory in San Jose, California, where he dons safety glasses and wields an array of saws and shears against EV chargers. The goal: to approximate the rash of vandalism sweeping the 65,000 US cords under ChargePoint’s care.

“It’s all over the country,” Wilmer says. “The types of stuff we’ve seen happen is just horrifying in terms of the way they go about it and how frequently it happens.”

ChargePoint isn’t alone. This year through June, nearly one in five US public charging attempts ended in failure, according to JD Power; roughly 10% of those aborted sessions were due to a damaged or missing cable. While some of the destruction is without agenda — the same spray-paint and baseball-bat havoc that affects vending machines and delivery robots — charging executives say much of the damage has a specific, profit-based motive: copper.

There have been similar reports of vandalism in Europe, and in May Instavolt Ltd. — a UK charger operator — warned of a crackdown on cord theft. But the mayhem comes at a particularly tough time in the US, where sales of electric cars are flagging. A reliable charging network is key to dousing drivers’ range anxiety, and charging companies are eager to disabuse EV-skeptical consumers of the notion that public stations are inconvenient, slow and often broken.

Vandalizing a public EV plug isn’t much more complicated than stealing a bicycle. Charging stations tend to be inconspicuous, tucked into the quiet corners of shopping centers and municipal parking lots. Almost all of them are unmanned, and cutting a cord can be as simple as severing it from the station with a hacksaw.

Vandalism is “front and center for us and has been really since the start of the year,” says Anthony Lambkin, vice president of operations at Electrify America, which manages about 1,000 charging stations in North America. In 2024 so far, vandals have cut 215 of the company’s cords, up from 79 in the year-earlier period.

FLO, which runs just under 3,700 charging stations in North America, has also seen an uptick in vandalism this year, though it says most damage to its cables is accidental. Recently, seven of the company’s fast-charging cords were cut in a single week.

Wilmer has that beat: On one day this summer, thieves cut multiple cords at the station just outside ChargePoint’s Silicon Valley headquarters. And across the company’s network, four in five vandalism cases involve cut cords. Nationwide, charging executives say the issue is more pronounced in urban centers, with particularly consistent problems in Las Vegas, Seattle, and Oakland, California.

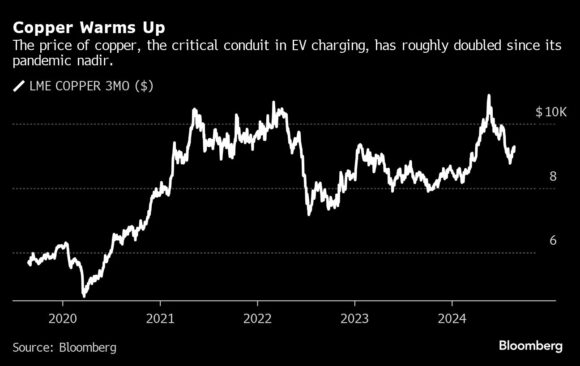

Many of these cord bandits are on the hunt for copper. The metal is a critical vein in the fast-growing circulatory system of public charging, and prices have roughly doubled since a nadir in early 2020. Construction, tech gadgets and the strengthening US economy at large are also driving up copper demand.

The profit motive is reflected in the nature of the vandalism, which is often more organized than opportunist. Groups of thieves will cut every cord in a station, taking it offline entirely. Electrify America has also seen copper wiring mined from its charging units, and from underground conduits. EVgo Inc., which operates nearly 1,000 US stations, has security footage of perpetrators wearing uniforms to make themselves look like utility workers or technicians.

“Ultimately, there needs to be a larger law enforcement response to this,” says Sara Rafalson, EVgo’s executive director of policy.

Stealing at scale may also be the only way for thieves to get a decent return on investment. One slow-charging cable, known as a Level 2 charger, contains about 5 pounds of copper; at the moment, that equates to about $21. A Level 3 cord — the kind found at fast-charging stations — has about twice as much.

“The financial reward hardly justifies the risk and effort involved,” says Travis Allan, chief legal and public affairs officer at FLO.

For charging companies, the theft can add up quickly: Level 2 cords cost about $700 apiece to replace, while fast-charging conduits can reach $4,000. Most charger operators are working on technological solutions to minimize those costs, including automated surveillance. FLO’s chargers, for example, have 200 different sensors — including one that can detect a cut cord. But it’s almost impossible to automatically catch every form of casual mayhem.

“It’s very tough to put an alarm on spray paint,” says Yann Benoit, senior director of charging operations at FLO.

Cameras and other proactive monitoring can also get prohibitively expensive, and raise privacy concerns. FLO is testing new chargers that have a camera inside — much like an ATM — but only plans to activate the cameras in areas with high levels of vandalism. Electrify America now has cameras at about 100 of its stations and is deploying speakers that will essentially holler at would-be thieves.

ChargePoint is leaning on drivers as its first line of defense. Last month, the company’s app began prompting users to flag busted stations, asking them to categorize the problem and submit a photo. Wilmer says the update will help the company identify and fix vandalized chargers more quickly, ideally in less than a day.

“We’ve put a ton of investment into this area,” he says, adding that the company is more focused on keeping chargers consistently operational for drivers than lowering its repair costs.

At its San Jose lab, ChargePoint is also examining how vandals execute their task, and what it might do to make that harder. Wilmer’s engineers scour YouTube for videos of thieves cracking bike locks — a process not unlike cord theft — and ChargePoint is among the companies racing to develop an uncuttable cord. It’s trickier than it sounds: Heavy-duty sheathing would help, but it also make the hoses heavier, less malleable and more difficult to cool.

In short, the vandals, at the moment, have the edge.

Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash

Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash  What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market

What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market  Preparing for an AI Native Future

Preparing for an AI Native Future  Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality