As residents of western North Carolina piece together their lives following Hurricane Helene, few will be able to rely on federal flood insurance to help them rebuild.

Roughly 1 in 200 single-family homes in the region is covered by the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), according to a Reuters analysis of federal government data – a far lower level of coverage than can be found in the coastal and riverside neighborhoods the program was designed to serve.

That is because the federal program is focused on the flood risks posed only by rising seas and swelling rivers, not the threat posed by the sort of extreme rainfall brought on by Helene.

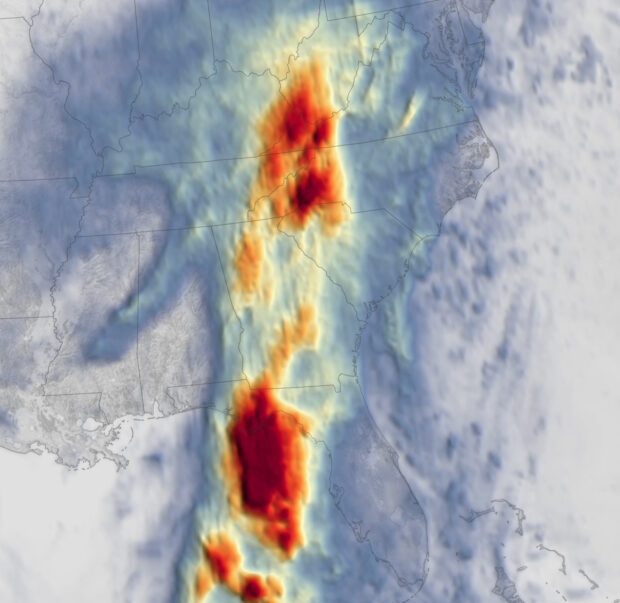

The storm dumped more than 35 centimeters (14 inches) of rain over three days onto western North Carolina, transforming mountainsides into mudslides and creeks into torrents.

“It’s horrendous,” said Aaron Smith, who said he was trying to figure out where to take his family after his home in the hamlet of Bat Cave was destroyed. “I don’t see anything to go back to.”

RISING RAIN RISKS

Asheville, the largest city in the flood-hit region, had in recent years developed a reputation as a climate refuge, drawing residents from more storm-prone areas.

Among the new arrivals: the federal government, which moved its national data center for environmental records there in 2015. The facility was knocked offline by Helene.

Private insurance companies see the area as relatively safe. The industry asked state regulators earlier this year to approve a 99 percent rate increase for coastal areas, but sought only a 4 percent hike for some of the mountain counties hit by the storm.

Helene has shown no place is immune to climate impacts, said Jesse Keenan, a Tulane University professor who studies climate migration. “There’s no such place as a climate haven,” he said.

Private insurers generally do not offer flood coverage. Instead, homeowners and businesses in flood-prone areas turn to the NFIP, which insures 4.7 million properties nationwide.

Heavy rainfall events, such as the one brought by Helene, are likely to become even more damaging with climate change as warmer air can hold more moisture.

Since 1900, precipitation in the United States has increased along with rising temperatures, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, and that rain and snow has increasingly fallen in intense bursts.

Mountain areas can be especially vulnerable to rain-triggered floods. A summer storm that lashed eastern Kentucky for four days in 2022 dropped up to 10 centimeters of rain per hour. The resulting floods swept away homes and killed 39 people.

RISKY MISMATCH

Despite the growing rainfall risks, the Federal Emergency Management Agency does not consider the risk of rain-induced flooding when it draws up maps that show where people must buy flood insurance in order to qualify for a federally backed home loan. Instead, agency scientists examine patterns of river flooding and coastal storm surges.

As a result, few residents outside of coastal or riverside areas are required to buy flood insurance.

The agency said that approach is set by law and said its maps should not be viewed as a prediction of where flooding will occur. “Where it can rain it can flood,” FEMA press secretary Daniel Llargues said.

The mismatch between coverage and exposure is especially stark in Appalachia, where rainfall – not ocean waves – poses the biggest flooding threat and steep mountainsides funnel rainwater into narrow river valleys, said climate scientist Jeremy Porter at First Street risk consultancy.

“That Appalachian region actually becomes the poster child for unknown flood risks across the country,” he said.

According to a Reuters analysis of First Street data, 16 percent of all residential and commercial properties in the 25 North Carolina counties most affected by the storm stood a one in four chance of flooding within 30 years – the same criteria used by FEMA to designate a flood zone.

Roughly 41 percent of all properties in North Carolina’s coastal areas face the same risk.

Federal flood coverage also varies widely by region.

While 43 percent of single-family homes in North Carolina’s coastal Dare County had NFIP policies, just 0.5 percent of homes had coverage in the western counties hardest hit by Helene, according to a Reuters analysis of federal flood insurance data and census data compiled by the University of Minnesota.

That reflects the fact that FEMA’s maps do not account for rainfall — leaving residents in mountainous areas unaware of their risk, said Carolyn Kousky, an economist at the Environmental Defense Fund.

FEMA should update its maps to reflect that risk, she said.

A 2022 survey by Fannie Mae found that only 37 percent of residents living in a flood plain knew they faced a high flood risk.

Residents affected by Helene who do not have that flood coverage will be able to apply for up to $30,000 in federal disaster aid, as well as loans from the Small Business Administration – though those can make up only a fraction of the $250,000 worth of coverage available through the federal flood program.

Some community leaders are already grappling with the expense of rebuilding.

“What I worry about is the cost and the time that’s going to be needed to restore this community,” Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer told Reuters on Tuesday.

(Reporting by Andy Sullivan, Grant Smith and Simon Jessop; Additional reporting by Sam Hunt; Editing by Katy Daigle, Benjamin Lesser and Daniel Wallis)

Preparing for an AI Native Future

Preparing for an AI Native Future  AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage

AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage  Chubb CEO Greenberg on Personal Insurance Affordability and Data Centers

Chubb CEO Greenberg on Personal Insurance Affordability and Data Centers  Nearly 26.2M Workers Are Expected to Miss Work on Super Bowl Monday

Nearly 26.2M Workers Are Expected to Miss Work on Super Bowl Monday