Severe rains bucketed down on central Europe, Africa, Shanghai and the U.S. Carolinas this week, underscoring the extreme ways in which climate change is altering the weather.

Different meteorological phenomena are behind the series of storms, according to climate scientists, though they agree an underlying factor for the supercharged rainfall is global warming writ large. Research has shown that hotter air is capable of carrying more moisture and is more likely to cause intense precipitation.

And it’s not just the amount of rain that falls, but where it lands. Emergency preparation, infrastructure and access to relief funds have led to vastly different outcomes—a reminder that the effects of climate change are not being felt equally across a warming world. At least 1,000 people have died in Africa, and millions of people have been displaced. In Europe, meanwhile, the toll is considerably lower, and government officials have already pledged vast sums of public funding to rebuilding.

“There are these fingerprints of climate change in these heavy rainfalls leading to these big floods,” said Hannah Cloke, a professor of hydrology at the University of Reading. “But we have to recognize that people have changed the landscape, made it more likely that people are in the way of these floods too.”

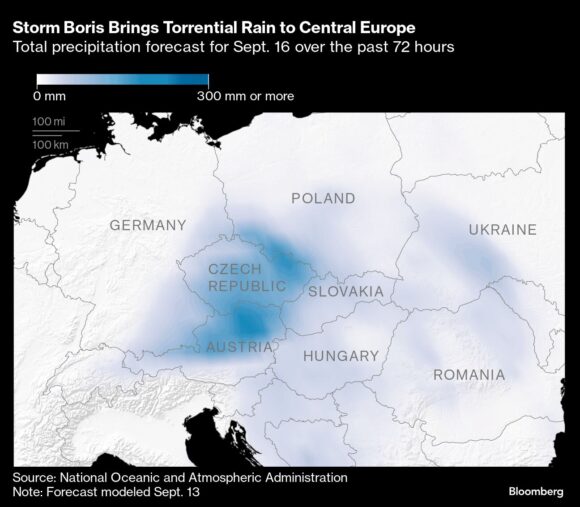

Storm Boris, a slow-moving system, began unleashing torrential rain across Poland, Czech Republic, Romania, Slovakia, Austria, Hungary and Germany last week. St Poelten, the capital of Lower Austria, saw 409 millimeters (16 inches) of rain over five days, almost double the previous five-day record. More than 20 people have died.

As the rains taper off in some areas, towns and villages are preparing for floodwaters to peak over the coming days due to river swelling. Several countries had already invested in control systems and retention reservoirs that are helping to curb some of the damage.

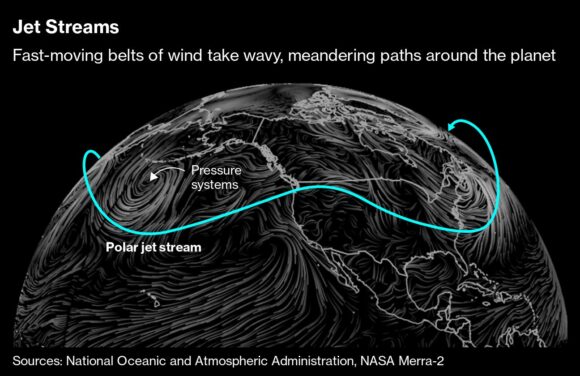

The region’s heavy rains can be traced back to the jet stream, a narrow and fast-moving ribbon of winds in the Earth’s upper atmosphere that travels from west to east. The jet stream is more orderly in the winter months, when cold air prevents its winds from wandering off track. In the summer and early fall, however, the system has a tendency to meander and “buckle,” sometimes becoming stuck on masses or warm air.

Current radar and satellite imaging show the “jet stream is clearly buckled in large, sharp meanders, causing stagnant weather systems around the Northern Hemisphere,” said Jennifer Francis, a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center based in Massachusetts. It’s not clear exactly what’s caused the jet stream to warp this season, she said, but “raging ocean heat waves” due to global warming were one culprit. Average sea surface temperatures were 0.96C (1.73F) above normal in August, the second-hottest month on record.

Scientists also concluded that human-caused climate change worsened severe rains across Germany and Belgium that caused catastrophic flooding in 2021. A cut-off low, which broke away from the jet stream, dragged moisture from the Mediterranean and slowly wrung it out across central Europe. That resulted in Germany’s costliest disaster on record, racking up a bill of $40 billion. This time, Europe was better prepared, with forecasters predicting historic rains days in advance and giving communities time to prepare.

That wasn’t the case in the US, where a historic rainstorm — which Francis also attributed to the buckled jet stream — took Atlantic coastal communities by surprise on Monday night. It unleashed record-breaking rainfall and tropical-storm force winds of 50 miles per hour in North Carolina and South Carolina. Volunteers with rain gauges reported up to 18 inches of rainfall in 12 hours, according to the US National Weather Service, which would make it a one-in-a-millennia rain event.

The downpours stemmed from a weather system that formed over the Atlantic basin, but ran out of runway and failed to coalesce into a full-blown hurricane or even a named storm before reaching the Carolina coast. Forecasters at the National Hurricane Center were still referring to the system as “Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight” right up until it touched land.

Despite the historic rainfall, flooding was largely limited to low-lying areas and coastal zones. “In many areas of the US, we’re seeing a clear trend toward more frequent and intense heavy rainfall events, but we’re not seeing an commensurate increase in flooding,” said Ben Cook, a climate scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. “That’s probably due to infrastructure developments,” he said, and how vegetation is changing or land surfaces are drying out.

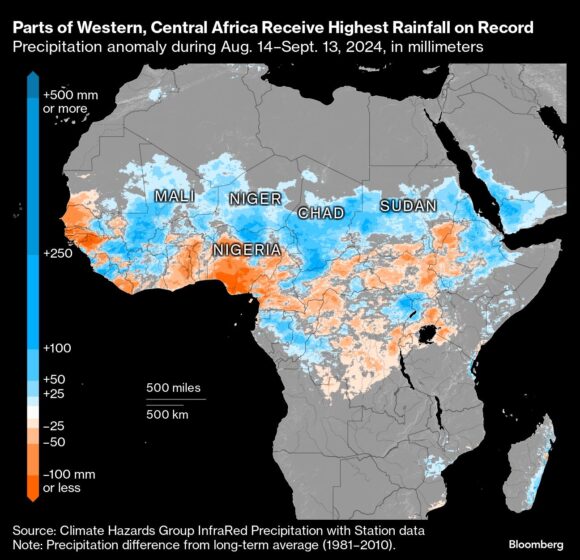

In western and central Africa, the rains have been driven by a distinct set of circumstances, with distinctly deadly effects.

At least 2.9 million people have been displaced from the western and central Sahel and neighboring countries since record-breaking rainfall arrived in early September. The rains have come during what’s traditionally the monsoon season. But it’s been far too much too fast, with one forecaster predicting the region will see 500 percent of its average annual September rainfall.

Friederike Otto, senior lecturer in climate science at Imperial College London, said the kind of heavy rainfall experienced in Africa is “more likely because of fossil-fuel-driven warming.” Earth’s average temperature is currently about 1.3 degrees Celsius higher than pre-industrial levels. That’s consistent with warming trends over the Sahel, a semi-arid region that touches the southern Sahara Desert and spans the continent from east to west.

Flooding has now affected at least 14 countries across the region, some of which were already struggling with food shortages and political instability. Excessive rainfall has destroyed Cameroonian cocoa plantations and disrupted grain production in Chad, where officials say thousands of livestock have also drowned.

“We fear that it’ll get worse, every year for the past four years rains have gotten stronger, more violent,” said Mamane Hadi, a 36-year-old farmer in Niger’s southern Zinder region who should be harvesting crops including dates, lettuce and squash at this time of year. “Everything has disappeared in the floods, there’s nothing left,” he said.

Meanwhile, China is bracing for another bout of heavy rain on and around Shanghai after Typhoon Bebinca hammered the city on Monday. It was the strongest storm to hit the financial center in more than 70 years, with winds so strong that it would have qualified as a Category 1 hurricane.

Authorities closed down transportation links across the metropolis of 25 million and suspended food delivery services to keep drivers safe. Flights out of Shanghai were canceled. Two people died, according to state media.

Bebinca was the latest in a parade of storms that has battered China, Vietnam, and Japan this year. On Sept. 6, Super Typhoon Yagi struck the Chinese island of Hainan with winds of 144 miles per hour and caused flooding across Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, a significant rice-growing region.

The impacts have been significant even though this year’s western Pacific typhoon season could be considered milder than usual, according to Jason Nicholls, a meteorologist with AccuWeather. Out of 14 named storms this year, just six have reached typhoon strength.

Where the storms are originating is more problematic for Pacific nations than the overall number of storms. The Pacific Ocean is struggling to transition to its cooler La Niña phase, which is pushing the starting point for typhoons and tropical storms further west across the basin — and closer to population centers in Japan, the Philippines, China, and Taiwan. Instead of curving toward the pole, more storm systems are striking land before drifting out to sea.

Tropical Storm Pulasan has now emerged on nearly the same track as Bebinca, which means more flooding to the water-logged area around Shanghai, Nicholls said. Fortunately, Bebinca stirred cool water up in the Pacific that will rob Pulasan of the fuel it needs to grow more powerful winds. To the south, tropical depression 16 has developed in the South China Sea and will menace Vietnam.

Many extreme weather events the world has seen in recent years have been worse than climate scientists predicted, according to Asher Minns, executive director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of East Anglia. That trend is likely to continue as greenhouse gas emissions keep rising and the planet keeps heating up.

These catastrophic events are “sort of running ahead of what it is that the global climate models and regional climate models would expect us to be seeing,” Minns said. “These should be a bit further in the future, but they’re happening now.”

Photograph: Typhoon Yagi approaches on Sept. 5, 2024 in Huizhou, Guangdong Province of China. Photo credit: VCG/Getty Images

Preparing for an AI Native Future

Preparing for an AI Native Future  Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster

Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster  Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality  How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll

How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll