Cities often get more rain and experience extreme rainfall more often compared to surrounding areas, a new study finds, a phenomenon that compounds other risk factors for urban flooding.

Of the more than 1,000 cities around the world that the researchers considered, 63 percent received more annual precipitation on average than outlying rural areas, according to an analysis of two decades of satellite data published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In some cases, the difference was more than half a foot per year. Many cities also saw more frequent and more dramatic extreme rainfall.

Urban areas are already vulnerable to flooding because of factors including impervious surfaces like roads and parking lots and inadequate drainage systems. What’s more, climate change is fueling heavier rainfall events — and the new study suggests cities are directly in the line of fire.

Urbanization shapes the weather in multiple ways, said Dev Niyogi, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at the University of Texas at Austin and one of the study’s authors. For one thing, cities tend to be hotter than rural areas, a phenomenon called the urban heat island effect. When warm air rises, it creates updrafts that can lead to increased cloud formation and rainfall.

The uneven urban landscape of tall buildings and hard infrastructure can slow local airflow or prolong rain. And the air above cities has a higher concentration of aerosols, meaning there are more tiny particles in the atmosphere to gather water around them into raindrops and fuel cloud formation.

“Cities can make a storm on steroids,” said Niyogi. “That’s how you are adding the risk for [an] increased flood.”

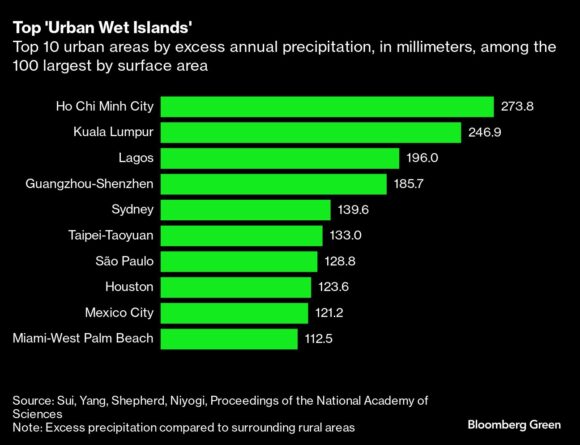

The effects of what Niyogi and his co-authors call “urban wet islands” can be dramatic. The urban area of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, saw 274 millimeters (about 11 inches) of additional yearly precipitation on average, compared to its rural fringes. Guangzhou-Shenzhen, China, got 186 millimeters extra, and Houston an added 124 millimeters.

The authors defined the cities based on satellite observations of land cover and then established three concentric zones around each, assuming that the most distant zone “lies out of the dominant range of city influence” on precipitation, they write.

A handful of urban areas, including Kyoto and (surprisingly) Seattle, were shown to be “dry islands” because they got less rain than the areas around them. Geography seemed to play a role in some cases, such as cities sitting in valleys that get less precipitation than nearby hills. The researchers also found that precipitation was higher downwind of cities, relative to surrounding areas, and lower in rural areas upwind of them.

Scientists have long known about urban heat islands. There’s rising awareness of urbanization’s other implications for local climates, and the new research is an “important step forward” in understanding the effect on rain, said William Solecki, a professor of geography and environmental science at Hunter College who was not involved in the study.

Past research has explored how various urban environments, from Atlanta to Beijing, shape precipitation. The new study suggests that the effect, like increased heat in cities, is a global phenomenon, Niyogi said.

The intensity of urban wet islands increased over time, the authors found, with the average disparity in precipitation for those areas nearly doubling between 2001 and 2020. Larger cities were more likely to be wet islands, a sign that urban development is fueling the anomalies.

Even as cities grow, understanding the conditions they’ll face in the future can help fortify them against flooding. Critical infrastructure can be built on higher floors in buildings, Solecki said. He also pointed to efforts to prioritize permeable surfaces and to build water retention areas, such as sunken basketball courts that fill with floodwater and slowly release it.

“We’re on a trajectory of dynamic change” in the climate, Solecki said. “Any information is going to be very valuable in helping designers and planners.”

Photograph: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; photo credit: Ian Teh/Bloomberg

Earnings Wrap-Up: AXIS Expanding Insurance Biz, Shrinking Re Book

Earnings Wrap-Up: AXIS Expanding Insurance Biz, Shrinking Re Book  AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage

AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage  Earnings Wrap: With AI-First Mindset, ‘Sky Is the Limit’ at The Hartford

Earnings Wrap: With AI-First Mindset, ‘Sky Is the Limit’ at The Hartford  Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk