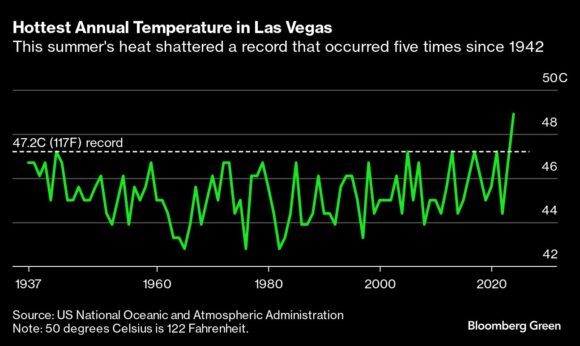

Las Vegas set a heat record of 117 degrees Fahrenheit (47.2C) in 1942, and for 82 years no weather system could budge it. Thermometers registered the same temperature four more times, all since 2005, without setting a new high. Then 2024 happened.

The heat record was broken — and not by just a little. On July 7, the temperature at Harry Reid Airport in Paradise, Nevada, jumped to 120F.

Records are breaking the world over this summer following a 13-month streak of hottest-ever monthly global average temperatures. At least two major scientific agencies recently determined that July set another high-temperature mark while also logging the two hottest days worldwide in recorded history. There’s now a greater than 95% chance this year beats 2023 as the hottest since data-keeping began.

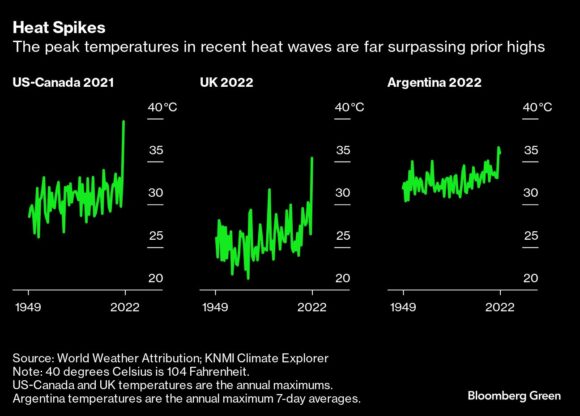

But it’s not just that heat records are being set more often than before. Many of these temperature spikes are breaking local records by noticeably large margins. And that’s fueling fresh interest among scientists who model future heating as the planet continues to rapidly warm.

Record-smashing extreme heat has become an expected consequence of the pace of climate change among scientists who study it. Climate scientists usually frame dangers by talking about the level of warming, comparing conditions that would develop after average temperatures rise by 2C or 3C. But when it comes to the scale of new heat records in coming decades, the rate of warming may have the upper hand.

It’s a fundamental question raised by the research of Erich Fischer, a climate scientist at ETH Zurich. Fischer began to wonder several years ago if the world was seeing records falling more dramatically. Simulating extreme heat waves in the US led him to a conclusion so unusual he initially rejected it. He observed in his data the possibility in coming decades of “record-shattering extremes, nearly impossible in the absence of warming,” he and other researchers wrote in a 2021 paper.

That analysis has held up against real-world events. Four weeks after a journal accepted his paper, western North America experienced an anomalous heat wave at the very scale he projected. A British Columbia village broke Canada’s 84-year-old heat record of 45C (113F) three days in a row, reaching 49.6C (121.3F). The next day, a wildfire leveled much of the town, killing two people. A team of scientists later declared it among the six most intense heat waves ever recorded.

“The climate currently behaves like a guy who would come and jump a meter farther than anyone before,” Fischer said. “You would think it’s an athlete on steroids.”

Fischer found that such extreme leaps might be up to seven times more common by 2050, compared with the last 30 years, if the world continues a high level of greenhouse gas emissions. That lines up with other findings about the big role climate change plays in these extra-large spikes. The Las Vegas heat in July was made 22 times more likely by the warming climate, according to research nonprofit Climate Central, while a springtime heat wave in Vietnam was 38 times more likely because of climate factors. Mali’s capital of Bamako set four daily high records in April during a month of heat made 90 times more likely by the changing climate.

As new extremes arrive, Fischer predicts previously rare high-end temperatures will become more commonplace. A 1-in-1,000-year heat wave any time between 1951 and 2019 will have shifted to a 1-in-100-year event by around 2020, according to his study. That not-so-unusual heat wave will move again to a 1-in-40-year event in the mid-2020s.

A small number of scientists are working on the question of runaway heat records. Fischer and others expect, based on their understanding of climate physics, to see examples accumulate in coming decades.

It’s not a trivial task to monitor the margins of new heat records, in part because there are so many ways to define a heat event. One-day maximum temperature? An average high over three days? And over how large an area? Even in well-monitored regions, including the US and Europe, the data are inconclusive.

Take the UK as an example. Temperatures hit 40C (104F) for the first time in 2022, and the number of days above 30C (86F) has more than tripled. Yet the amount of data that scientists would need to determine climate change is causing a leap in margins is immense, said Mike Kendon of the UK Met Office.

For now, there aren’t enough outlier weather episodes for the phenomenon to be conclusively observed in real-world data rather than projected in scientific models. But the examples that have occurred just in the last year focus the imagination: Africa’s hottest-ever June temperature of 50.9C (123.6F) descended on Aswan in Egypt, smashing a 63-year-old national record by 0.6C. Costa Rica hit 41.5C (106.7F) in March, 1.1C higher than its 2010 mark.

It all adds up to big heat jumps globally. Last September beat the worldwide record by such a vast margin that a US climate scientist memorably called it “absolutely gobsmackingly bananas.”

Mingfang Ting, a climate professor at Columbia University, is among the researchers who expects future data to show a shift in the margins. “My personal feeling is that I think we are seeing it, but we don’t have a long enough record to prove that yet,” she said.

Photograph: A dried up pond in Bac Lieu Province, Vietnam. The country endured a springtime heat wave, which was made far more likely by climate change. Photo credit: Linh Pham/Bloomberg

What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market

What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market  Nearly 26.2M Workers Are Expected to Miss Work on Super Bowl Monday

Nearly 26.2M Workers Are Expected to Miss Work on Super Bowl Monday  Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash

Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash  Modern Underwriting Technology: Decisive Steps to Successful Implementation

Modern Underwriting Technology: Decisive Steps to Successful Implementation