Changes in the mpox virus are just the latest challenge facing disease trackers trying to contain an outbreak of the virus that’s become a global health emergency.

The surge of cases is centered in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a country roughly the size of Western Europe that’s been wracked by decades-long conflict, severe poverty and malnutrition as well as camps housing hundreds of thousands of displaced people. Now, just like the coronavirus, influenza and the many other pathogens that pose persistent risks, the virus that causes mpox is mutating, further complicating the effort to track its spread.

With this outbreak, mpox had “a big evolutionary jump,” said Tulio de Oliveira, director of Stellenbosch University’s Centre for Epidemic Response and Innovation near Cape Town. “We have every reason to believe that there are many more cases that we have not detected.” (Editor’s note: Mpox was formerly known as the monkey pox virus).

Why Is Mpox an Emergency Again, and How Worried Should I Be?

The last big surge of mpox in 2022 was also declared a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization in Geneva. That was caused by a milder strain of the virus known as clade IIb. The new mutated strain is related to a more virulent version called clade I that appears to be spreading more quickly in children and adolescents, as well as through sexual contact.

The DRC has dealt with outbreaks of diseases such as Ebola, cholera and malaria before — often with little global assistance. In the current mpox outbreak, the government last month reported an exponential increase in infections. The country has developed a vaccination strategy, Roger Kamba, Congo’s public health minister, said in a video posted on the X social media site.

In a later briefing, broadcast on national television, he said 2.5 million people will need to be vaccinated to stop the spread of the disease. For that to happen, 3.5 million doses will be required and that will cost hundreds of millions of dollars, he added, urging to the international community to provide assistance.

While not as deadly as smallpox, mpox still is lethal in about 3% to 6% of reported cases. Lesions from the infection can cause blindness, disfigurement and severe pregnancy complications. More than 500 deaths have been reported in the DRC from the disease since the beginning of the year.

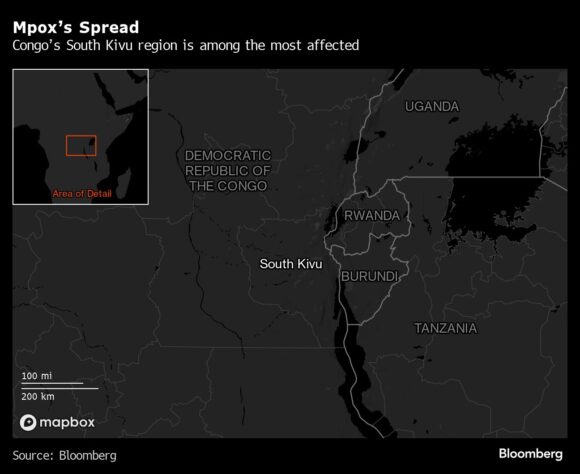

Health systems in eastern DRC, where transmission is highest, were extremely fragile even before this outbreak and a scarcity of staff and medical supplies further complicate efforts to contain the disease.

Now as this strain has “emerged in eastern DRC, where there are mining towns with a large number of sex workers — and it’s very close to the borders of multiple countries,” including Rwanda and Uganda, the risk is spreading, Stellenbosch’s de Oliveira said. He ran a team of scientists that identified the omicron variant of the coronavirus.

Another concern is the possibility that some mpox patients are also infected with HIV, which cuts the body’s ability to fight disease. Africa has the world’s biggest number of HIV infections. Efforts to contain mpox should focus on improving knowledge among communities of its existence, getting timely diagnostics run and making vaccines available, Oliveira said.

While mpox has spilled over from its animal hosts to infect humans in West and Central Africa with increasing frequency since the 1970s, it’s “when it enters more direct transmission between humans then we get worried,” De Oliveira said.

Top photo: A doctor checks on a patient with sores caused by a monkeypox infection in the isolation area for monkeypox patients at the Arzobispo Loayza hospital, in Lima, Peru on August 16, 2022. Photographer: Ernesto Benavides/AFP/Getty Images

Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid

Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid  Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages

Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages  Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb

Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb  Nearly 26.2M Workers Are Expected to Miss Work on Super Bowl Monday

Nearly 26.2M Workers Are Expected to Miss Work on Super Bowl Monday