Under the blazing Adriatic sun, life almost stopped in Montenegro’s capital Podgorica earlier this summer. Cars and buses were stuck in gridlock as traffic lights went out, the internet crashed, and security alarms blared in reaction to a sudden loss of power supply.

“After one hour without electricity, we were on the verge of panic because it was getting unbearable,” said Drago Martinovic, a 61-year-old retired police officer. “I’m afraid it could last longer if it happens again.”

The bad news for Martinovic and hundreds of millions of people around the world is that the risk of outages is getting worse. Hotter summers mean spikes in demand for cooling, as high temperatures cause wires to sag and risk sparking forest fires. Upgrades to power infrastructure haven’t kept pace, even as efforts to reduce use of fossil fuels make electricity distribution more crucial.

Triggered by a surge in consumption and unstable supply links, the blackout in Montenegro in late June knocked out grids at neighboring countries and wreaked havoc on households, hospitals and beach bars. The incident in the Balkans has been repeated around the world.

Millions of households in Houston suffered blackouts in the aftermath of Hurricane Beryl last week, losing air conditioning as sweltering heat followed the storm. Hitting emerging and developed economies, outages from Ecuador to India in recent weeks offer a foretaste of coming disruption.

The climate crisis exposes electricity networks to flash floods ripping down transmission towers, droughts drying up hydro reservoirs and demand spikes from cooling during searing heat.

“The whole power system was built and designed in one climatic era and now is being asked to work in a different climatic era,” said Michael Webber, a professor of energy at the University of Texas at Austin. “It just means more things can go wrong.”

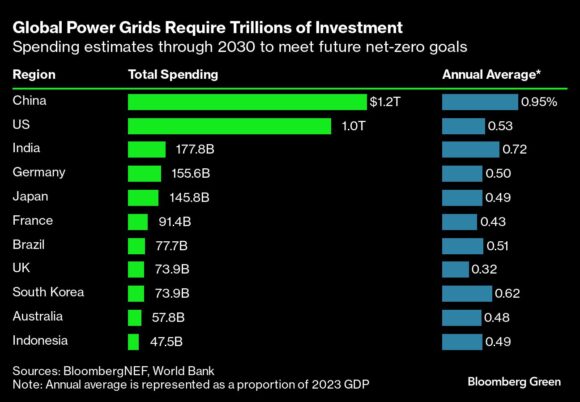

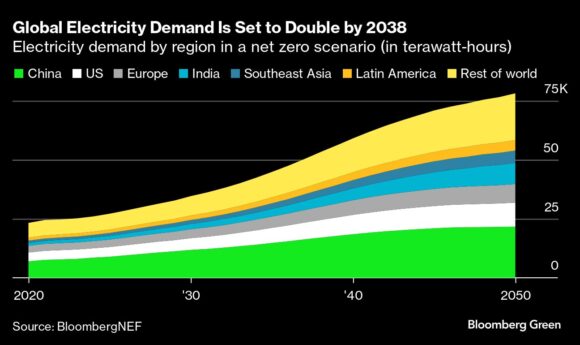

Unstable networks create instability for businesses, roil politics and threaten lives. Expanding the grid will cost about $24.1 trillion to meet net-zero goals by 2050, outpacing the investment needed in renewable-power capacity, according to BloombergNEF. Because of their vast areas and high energy use, the US and China face the biggest bills, but no country is spared.

Most blackouts occur when big chunks of supply or demand come on or off suddenly. Damage from storms, a burst of renewable generation or spikes in usage can all cause outages where the network isn’t resilient enough.

Climate change expands vulnerabilities beyond developing economies. The issues have recently hit more mid-tier countries including energy-rich Mexico and Kuwait as well as importers like Albania.

“As temperatures and access to air conditioning increases, it will put the grid under more strain,” said Felicia Aminoff, an analyst at BNEF. “We have already seen an increase in summer peak demand in certain European countries, such as Greece, as well as in the Middle East.”

A common theme behind grid issues is poor planning. In Kuwait, residents of one of the world’s richest countries had to endure rolling outages in June. Grid operators deliberately shut down parts of the grid to prevent a total blackout as power plants struggled to meet a demand surge when temperatures exceeded 50 degrees Celsius (122F). The incident led to fire departments getting inundated with calls to rescue people stuck in elevators.

The OPEC member has warned it may be forced to schedule further blackouts to prevent a breakdown in the system. “No one understood the importance of taking preventive measures,” said Fuad Al-Own, a former official at Kuwait’s electricity and water ministry. “You have to plan years in advance.”

While Kuwait can tap massive oil revenue to support grid investment, other countries aren’t so lucky.

In Ecuador, subway passengers had to abandon stuck trains and walk to stations through the unlit underground tunnels after the South American country’s worst outage in two decades in June.

Although Ecuador has bigger oil reserves than Mexico, it’s heavily indebted and reliant on the International Monetary Fund and other multilateral lenders for financing. Some of its problems are related to ill-planned projects like the $3 billion Coca-Codo Sinclair facility.

The 1,500-megawatt hydro-power plant normally supplies about a quarter of the country’s electricity, but has become a source of insecurity less than a decade after it went online. It suffered more than a dozen outages in the first half of 2024, and over 7,000 cracks have been discovered in funnels leading to the turbines.

When Coca-Codo Sinclair went offline last month due to heavy rain, supply from power plants elsewhere relied on a single high-voltage line that went down, taking all of the nation’s electricity with it. Ecuador had been forewarned of this risk by a 2004 blackout but never built the recommended redundancies.

Climate change affects power distribution in lots of ways. Extreme heat increases demand for cooling, while reducing the efficiency of solar panels, crimping supply. High temperatures can cause lines to sag and transformers to overheat, leading to equipment failing and increasing risks of fires.

As temperatures increase, grids will need to be more resilient, including storage to handle demand surges and supply disruptions. John Pettigrew, head of the UK’s National Grid, has also called for a “super-supergrid” — an even higher voltage network that connects countries.

In Mexico, blackouts have become more common as summers become hotter and drier, and a booming economy pushes power grids to the brink. The issues prod businesses into expensive workarounds to secure operations, mainly through the use of diesel-fired generators — a common practice across many countries with unstable electric systems.

Outages in the northern city of Chihuahua in June cut electricity to water pumps, halting supply for over 70,000 people over the course of two weeks. The rising frequency of the disruptions means dairy farmers and cheese manufacturers in the region have to spend as much as 50,000 pesos (about $2,700) a day on fuel for generators to power milking and refrigeration equipment, according to local news reports.

Mexico’s blackouts come after outgoing President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador opted to favor the domestic oil industry when it’s come to energy investments, largely cutting off the electricity sector. The lack of spending is now hurting Mexico’s investment prospects as a lack of reliable power becomes a hindrance.

A heatwave in May sparked outages across 21 states in Mexico, interrupting production at a Volkswagen AG manufacturing plant in Puebla for four hours. The same plant suffered another outage in June.

To address the crisis, President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum, a climate scientist with a doctorate in energy engineering, has pledged $13.6 billion to build renewable-power capacity, gas-fired plants and new transmission lines. But that’s less than half of the $38 billion needed to keep up with growing demand over the next five years, according to analyst estimates.

Grid strain has also been a concern north of the border. US network operators have struggled to keep the lights on as extreme weather has exposed vulnerabilities in an aging power delivery system.

California suffered brief rolling blackouts in 2020 and 2022 during extreme summer heat waves. And Texas’ grid collapsed in February 2021, when a severe winter storm caused a widespread failure of electricity generators, causing 246 deaths and more than $195 billion in property damage.

In countries that already had poor systems, climate change exacerbates the issues. A $1.3 billion undersea link was opened between Italy and Montenegro in 2019, but its capacity is already seen as insufficient and a second is under consideration.

The existing network was unable to prevent a major blackout across four Balkan countries including Bosnia-Herzegovina and much of the Croatian coast in June, affecting 4 million people. Consumption surged as temperatures hovered near 40C, causing one system after another to fail.

A forest fire in the Balkan region likely contributed to the malfunction, knocking out cross-border inteconnectors, affecting multiple countries, including Albania whose reliance on hydro power make it vulnerable to increasingly hot, dry weather.

“We continue to be in a high-risk zone,” said Belinda Balluku, the country’s energy minister, adding that authorities in the region are coordinating operations and doing everything they can to “keep the network safe.”

Photograph: A downed power line in Houston following Hurricane Beryl, on July 9, 2024; Photo credit: Mark Felix/Bloomberg

20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut

20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut  Preparing for an AI Native Future

Preparing for an AI Native Future  Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs

Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs  How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll

How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll