All the major indicators of climate change smashed historic records last year, with some rising so steeply that the United Nations’ World Meteorological Organization warned they were “off the charts.”

The lives of millions of people were upended by natural disasters made worse by climate change, with countries everywhere struggling to cope with billions of dollars in economic losses, according to the WMO’s annual State of the Global Climate report for 2023.

“Changes are speeding up,” said UN secretary general António Guterres in a statement. “Sirens are blaring across all major indicators—some records aren’t just chart-topping, they’re chart-busting.”

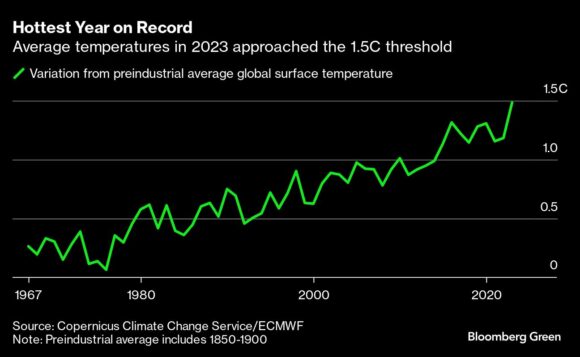

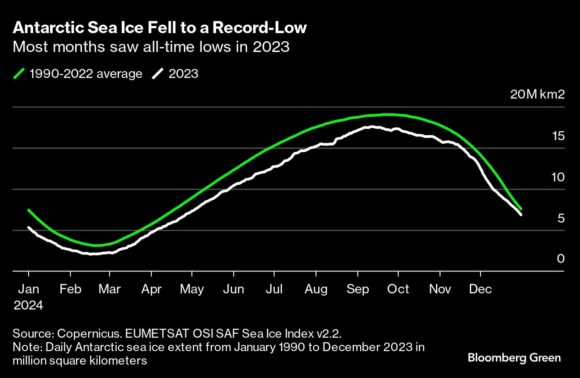

During the warmest year on record — with global average temperatures 1.45C higher than in pre-industrial times — Antarctic sea ice extent fell to the lowest ever registered while glaciers lost an unprecedented amount of ice. Record-setting marine heat waves whipped 90% of the planet’s oceans while floods, drought and wildfires intensified on land.

These impacts worsened every crisis humanity is facing. The number of acutely food insecure people worldwide has more than doubled in recent years, from 149 million people before the coronavirus pandemic to 333 million last year. And extreme weather events continued to trigger population displacement last year.

“Climate change is about much more than temperatures,” said Celeste Saulo, the WMO’s secretary general. “The climate crisis is the defining challenge that humanity faces and is closely intertwined with the inequality crisis.”

However, there’s a glimmer of hope, the WMO report noted. New renewable energy capacity — mainly driven by solar, wind and hydro power — rose by almost 50% in 2023 compared to the previous year.

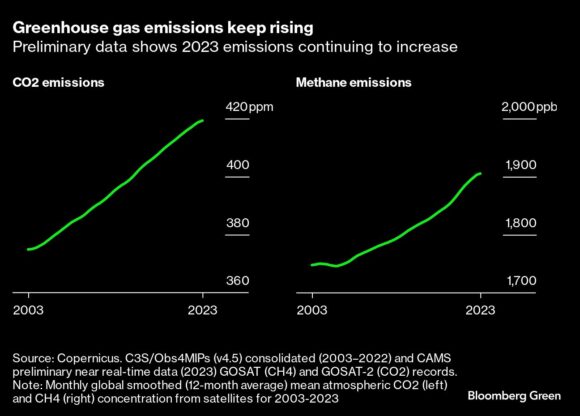

At the COP28 summit in Dubai last year, countries committed to tripling the planet’s renewable power capacity to at least 11,000 gigawatts by 2030, as well as doubling the rate of energy efficiency by the end of this decade. Leaders also agreed to transition away from fossil fuels, which is seen as a necessary step toward eliminating net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

But that target is still a long way away, the WMO’s report noted. Real-time data from specific locations shows concentrations of the main greenhouse gases continuing to increase in 2023 after reaching a new record-high in 2022. Levels of carbon dioxide are 50% higher than during the pre-industrial era, and the gas’ long lifetime in the atmosphere means temperatures will continue to rise for years to come.

Marine heat waves are particularly worrying because oceans have stored over 90% of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. As a result, the Earth hasn’t warmed as fast as it could have. But scientists are concerned that the ocean’s sponge-like capacity might have reached a tipping point, with global average sea surface temperatures breaking records by wide margins multiple months last year.

That extreme level of warming is expected to continue, leading to a change that’ll be irreversible on scales of hundreds to thousands of years, the WMO report said. Ocean acidification, which can be deadly for corals and other marine life, increased because of the higher amount of carbon dioxide in the water.

Top photograph: Ice forming from the window of an airplane heading from Iqaluit to Pond Inlet, Nunavut, Canada, on Wednesday, Nov. 10, 2021. The Earth’s poles are warming faster than elsewhere, with the North Pole heating up about twice as fast as the rest of Earth for the last 30 years.

Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb

Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb  Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk  Nearly 26.2M Workers Are Expected to Miss Work on Super Bowl Monday

Nearly 26.2M Workers Are Expected to Miss Work on Super Bowl Monday  What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market

What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market