FedEx Corp. is pressuring delivery contractors to improve safety after mounting accidents helped trigger a near-tripling of insurance costs over the decade.

FedEx is requiring contractors that deliver packages on behalf of the company’s Ground unit to install vehicle cameras and sensors, enhance training and pay penalties if they incur too many accidents, according to FedEx memos to contractors. A low safety score can also expose these delivery companies to competing bids for their routes and jeopardize their entire business.

The safety crusade is key to Chief Executive Officer Raj Subramaniam’s plan to combine the company’s Ground and Express units into a seamless network. The company is already testing contractors’ ability in 20 markets to meet the stricter delivery deadlines that come with many Express packages. Unlike the Ground unit, Express directly employs drivers, owns the trucks and has a much better safety record as measured by fatal crashes.

The Ground business that employs about 6,000 delivery and big-rig contractors had 89 fatal accidents in the U.S. over the last two years, according to US Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration data as of Aug. 2. FedEx Express had seven fatal crashes during the same period.

Main rival United Parcel Service Inc. had 66 fatal accidents over the same period even as UPS drivers logged more miles, according the federal data.

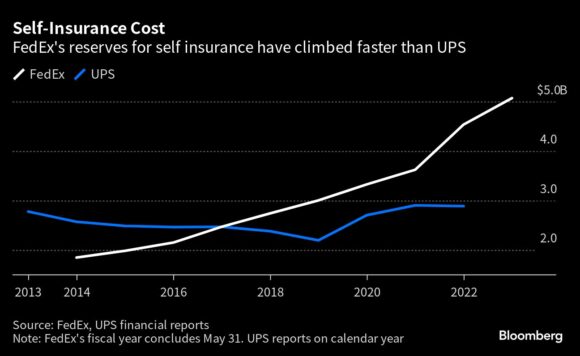

The safety issues are hurting FedEx’s bottom line. The amount of self-insurance reserves FedEx sets aside to cover claims surpassed $5 billion for the first time during the fiscal year ending May 31, up from $2.47 billion in 2017 and $1.8 billion a decade ago, according to company records. FedEx Ground provides insurance coverage for its contractors, who pay deductibles.

UPS, which delivers roughly 60 percent more packages than FedEx, had self-insurance reserves of $2.9 billion last year, a slight increase from $2.8 billion a decade ago, company filings showed. Large carriers, including FedEx and UPS, often are self-insured, which means they set aside funds to pay for claims instead of purchasing insurance.

In response to questions from Bloomberg News, FedEx said that “safety is paramount in every aspect of our business” and that its contractors share in this commitment.

“Through the implementation of initiatives that promote the use of technology and provide enhanced visibility into service provider safety results, we are supporting an environment of continuous improvement, increased visibility and accountability to ensure safety remains at the forefront of everything we do,” FedEx said in its emailed statement.

In a recent meeting with contractors in Orlando, FedEx executives said safety was a top priority and that the push to adopt technology has helped bring down accidents as a percentage of miles driven. Coming next is an artificial intelligence-based system that detects when a driver is distracted and sends real-time alerts, Clarence Dozier, FedEx Ground vice president of safety, said at the meeting.

“It’s clear that safety technologies help reduce accidents,” Dozier said, according to an audio tape of the early-August FedEx event that was shared with Bloomberg.

More than 10 current and former delivery contractors said that despite the focus on using tech and monetary incentives to boost safety, FedEx isn’t addressing the structural challenge of high driver turnover, which can lead to more accidents. They asked not to be identified because of strict non-disclosure clauses in their contracts with FedEx.

These contractors also said that, in their experience, accidents tend to involve new drivers in their first months on the job, and that FedEx doesn’t pay them enough to increase driver wages to entice drivers to stay for the long term and gain experience.

Several studies, including one by Virginia Tech Transportation Institute in 2020 and sponsored by the FMCSA, have shown that in general commercial drivers with more experience on the job are safer.

FedEx declined to provide data on driver turnover. At Ground, the churn is constant, averaging about 30-40 percent annually, according to Route Consultant, a firm that gathers data on contractors through the brokerage of sales of FedEx contractor delivery areas.

“FedEx Ground is constantly seeking feedback from service providers and evaluating the terms of our agreements to ensure that they take into account current market conditions as appropriate,” FedEx said in in response to questions about contractor concerns. “We are committed to maintaining an environment where service providers can deliver safe, and outstanding service in the communities where we operate.”

Instead of addressing the turnover problem, the company is reducing the terms and duration of contracts, contractors said, making it even harder for them to boost wages and invest in their fleets. Steve Justus, who owned a FedEx contractor for more than two decades, walked away from the business earlier this year after he said FedEx refused to pay more for deliveries even as inflation on fuel, tires, maintenance and other things ate away his profits.

“I was losing money every week,” said Justus, who said he’s now selling his trucks to pay creditors.

Generally, FedEx Ground contractors are small delivery companies. Top earners had annual revenue of about $33 million, with an average revenue per business of $2.3 million, according to a slide presentation from the Orlando meeting.

Justus said he offered new drivers starting wages of $18 an hour and quickly bumped that up to $20 for those who stayed. Good drivers are often poached by other contractors, he said. Driver pay varies depending on the area of the country and typically ranges from $15 to $25 an hour, according to the recruiting firm Bright Flag Recruiting.

“My veteran drivers were there six months,” he said. “I’d be lucky to keep them for a couple of years.”

FedEx declined to comment on contractors’ claims of high turnover or the pay rate for Ground drivers. FedEx doesn’t control how much contractors pay drivers. Even if the company paid contractors more, it’s not certain that extra money would flow to the drivers.

During a gathering of FedEx contractors in Las Vegas at the end of July, a hot topic was UPS’s tentative labor agreement that will pay drivers $49 an hour, plus full pension and health benefits, after four years on the job. It’s not unusual for UPS full-time drivers, a coveted position within the company, to stay aboard for decades. Many first had to show their initiative by loading packages before getting a chance to try out as a driver.

Turnover for UPS drivers, excluding retirements, is well below 1 percent a year, according to the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, which represents those unionized drivers. UPS said that 49 percent of its full-time delivery drivers have been with the company for at least 15 years.

FedEx contractors can’t compete with UPS wages and benefits, said Toni Tovi, who managed Ground contractor-delivery routes for two years before founding Bright Flag Recruiting, a worker recruiting firm. FedEx has courted heavier packages and expanded service to Sundays, increasing strain on drivers, she said. Additionally, Ground drivers can be left waiting at FedEx terminals for packages to be loaded on their trucks or end up doing it themselves. Contractors said those conditions make it harder to keep drivers.

“They need to pay their contractors more,” said Tovi, whose client base includes about 450 FedEx contractors. “Everything trickles down from that.”

Although FedEx Ground drivers make less than half of their counterparts at UPS, operating margins at Ground were 9.4 percent on a trailing-12 months basis, compared with 10.4 percent for UPS’s U.S. domestic unit. The lower driver pay at FedEx Ground masks inefficiencies such as the friction-filled hand-off of packages at terminals, and higher costs associated with covering for contractors when they fail or quit, the delivery business owners said.

Ground driver wages of $20 an hour once were higher than a lot of work that didn’t require technical training or a university degree. But the pandemic and the labor shortage it spawned drove up wages in many sectors and now there are less strenuous jobs that pay the same or more, said Adi Karamcheti, a former FedEx executive who now works for shipping consultancy Shipware LLC. It’s unclear if FedEx can resolve its safety problems while its contractors pay drivers so much less than UPS, he said.

“There are going to be morale and hiring issues at FedEx, particularly as long as there are other good-paying jobs available,” Karamcheti said, referring to the contractors who deliver for FedEx.

Photo: FedEx Corp. Ground trucks drives through Jeffersonville, Indiana in 2021. Photographer: Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg

Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs

Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs  Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster

Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster  20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut

20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut  Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes

Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes