Between the time Tropical Storm Ian moved from Florida on Thursday evening and the time it centered as a post-tropical cyclone near Myrtle Beach, S.C., early on Friday night, damage estimates from insurance risk modelers grew $16 billion.

That $16 billion one-day jump in loss estimates from two different modelers—CoreLogic and Karen Clark & Company—is coincidentally equivalent to private insured losses (in 2022 dollars) from an earlier Southeast U.S. storm event: 2004’s Hurricane Charley.

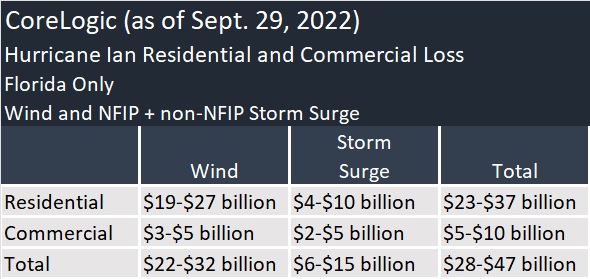

Just before 9 p.m. EDT on Sept. 29, more than a day after Ian made its first landfall as a Category 4 hurricane in Cayo Costa, Fla., CoreLogic announced its first estimates of insured losses for residential and commercial properties just in the state of Florida, putting the high-end estimate at $47 billion and the low at $28 billion.On Friday, at about 4 p.m. in the afternoon, roughly two hours after Ian made its third and final U.S. landfall as a Category 1 hurricane in Georgetown, S.C., KCC published a flash estimate of $63 billion in insured losses for the U.S. and the Caribbean–$16 billion higher than CoreLogic’s high-end figure.

This morning, Verisk announced an estimate of insured losses to onshore property in the range of $42-$57 billion but said that impacts of certain excluded items—litigation, social inflation and losses to the National Flood Insurance Program—could cause the total insured industry loss to exceed $60 billion.

All of the estimates include insured building, contents and business interruption losses to residential and commercial properties from wind and storm surge, as well as insured auto losses.

KCC estimates privately insured losses only. In addition to wind and storm surge, the KCC flash estimate includes a provision for privately insured inland flooding losses while excluding National Flood Insurance Program losses.

Verisk’s estimate, from Verisk Extreme Event Solutions, also includes privately insured inland flood losses resulting from Ian’s landfalls in both Florida and South Carolina, but not NFIP losses.

During a webinar on Friday, CoreLogic said that its range of estimates does include some NFIP losses, encompassing both NFIP and non-NFIP storm surge in addition to wind losses. The CoreLogic estimates, however, do not include a provision for inland flood losses or for states other than Florida.

CoreLogic’s analysis was based on the Sept. 29, 8 a.m. PT (5 a.m. EDT) National Hurricane Center advisory of the storm, which was issued when tropical storm Ian was positioned on Florida’s east central coast and had not yet reformed as a hurricane that made landfall in South Carolina. CoreLogic plans to produce flood loss estimates this week.

Another key difference to bear in mind when comparing the KCC with CoreLogic and Verisk estimates is that KCC’s estimates and Verisk’s estimates include provisions for estimated demand surge—post-loss amplification related to demand exceeding supply of materials and labor. The CoreLogic estimates do not.

“In nominal dollars, Hurricane Ian will be the largest hurricane loss in Florida history. The total economic damage will be well over $100 billion, including uninsured properties, damage to infrastructure, and other cleanup and recovery costs,” KCC said in a statement delivering the $63 billion estimate, which does not include estimates of uninsured wind or flood losses, NFIP losses, or loss estimate for destroyed boats and offshore property.

Breaking It Down

KCC did not provide any breakdown of the loss estimate for residential vs. commercial property or wind vs. water. The announcement of the flash estimate, however, does note that $200 million is expected from the Caribbean, with the rest of the $63 billion in privately insured loss attributable to wind, storm surge and inland flood perils in the U.S.

In breaking down its estimate, Verisk said wind damage of $38-$51 billion comprises the majority of the loss estimate. Storm surge (excluding losses from the NFIP) accounts for $3-$5.5 billion of the loss estimate, and inland flood less than $1 billion. Verisk estimates that roughly 1 percent of the total industry loss will come from the impacts of Ian’s South Carolina landfall.

CoreLogic delivered both residential vs. commercial and wind vs. water splits for its Florida-only range of estimates.

NFIP losses are the bulk of what comes up under “residential storm surge,” said David Smith, senior leader, science and analytics, highlighting the $4-$10 billion range there.

Rapid intensification of the event, he said, helped to keep that range lower than it could have been. “If [Ian] had been Category 4 strength for many, many hours or days ahead of landfall, that would lead to even higher surge than we saw,” he said.

Strong building codes may be another mitigating factor that will prove to ultimately soften the blow of Ian’s winds for insurers, Smith said, noting one set of building codes that took effect after Hurricane Andrew for properties building in 1996 or later, and another one for properties built in 2003 later. The hard-hit Fort Myers area has been rapidly growing, so a lot of the construction is newer and subject to those codes, he said.

In particular, areas hit by Hurricane Charley in 2004 have been rebuilt, he said, noting that Ian made landfall at almost the same place that Charley did. “These building codes do work,” he said.

Still, “this is likely to be the most significant loss event since Hurricane Andrew in Florida…”

“By point of comparison, Hurricane Charley, if it were to happen again today, would be something on the order of $16 billion on the private insured loss—so roughly half of what we’re projecting here for Ian, and that difference is largely just [due to] the breadth of the wind field [of Ian]. They came ashore at similar intensities—Category 4—but the wind field [being] four-times broader is a real big deal here,” he said.

What It Looks Like

Comparing events another way earlier in the webinar, CoreLogic catastrophe risk expert Tom Larsen showed the distribution of residential properties in various wind speed bands for Hurricanes Andrew, Wilma, Charley and Ian. Only Andrew and Ian had properties falling in areas that experienced “extreme winds” of 131-150 mph. While Andrew, Charley and Ian all had properties impacted by “extensive” 111-130 mph, for Ian, over 325,000 single and multifamily homes were in the areas experiencing “extensive” wind speeds during Ian, compared to roughly 265,000 for Hurricane Andrew and less than 30,000 for Charley.

“Hurricane Andrew was notable for the images of homes reduced to nothing but foundation slabs,” Larsen recalled, contrasting Wilma, where the majority of homes were in the “minimal” 74-95 mph wind speed band and images of blue tarps covering the roofs” told the story of that 2005 storm. “Homes were not totally destroyed, but roofs were damaged,” he said.

With roughly 270,000 homes in areas experiencing “minimal” and “moderate” wind speeds, “the story on Ian is not written yet,” Larsen said, suggesting the possibility of both slabs and tarps. “Better building codes and improved claim responses will be key here.”

Verisk reported wind losses around the areas where Ian made landfall in southwest Florida, ranging from significant loss of roof covers in residential homes to torn up roof membranes in commercial structures.

On Florida’s west coast, Verisk said surge collapsed several rows of beachfront residential homes, with some being dislodged from their foundations. In addition, manufactured home parks in southwest Florida saw massive damage including loss of roofs, damage to wall siding and near total destruction.

Litigation, Inflation and Demand Surge

In addition to CoreLogic, KCC and Verisk, at least two rating agencies have published reports with ranges of estimates. On Thursday afternoon, Fitch published an initial estimate of insured losses in the $25-$40 billion range for Florida only. On Friday afternoon, S&P Global Ratings said that it expects Hurricane Ian to result in $30-$40 billion of insured losses, setting a range at the upper end of pre-landfall estimates of $15-$40 billion from various sources.

(Editor’s Note: Guy Carpenter, for example, on Sept. 26 used Ian’s then-projected storm track to simulate losses from four historical events with similar tracks—Hurricane Gladys, a Category 2 storm in 1958, providing a low estimate of $15 billion, and three others ranging from Cat 2 to Cat 3, providing a high-end estimate of $35 billion.)

Like Fitch, S&P said U.S. P/C insurers that have financial strength ratings from the rating agency are well positioned to absorb losses from Ian, adding that ceded losses should remain within the annual catastrophe budgets of reinsurers. Ratings should remain largely unaffected by the hurricane, both firms said. S&P said roughly 40 percent of property-exposed lines of business in Florida are written by primary carriers rated by S&P. And both firms said that smaller unrated Florida specialists, filling the void left by larger national carriers that exited the catastrophe-prone state, rely heavily on reinsurers.

Only one of the reports with published estimates—the KCC report—refers to specifically including estimated impacts of both excessive litigation in Florida and of estimated demand surge.

“Over the past few years, KCC experts have analyzed the trends in litigated claims in Florida and other states. While legislative and policy changes should help to reduce the proportion of litigated claims relative to Hurricane Irma, the large proportion of properties with both wind and water damage may induce more litigation. The KCC estimate includes a comparable proportion of excess litigation as occurred in Hurricane Irma,” the report says.

The Verisk estimate reflects the impacts of inflation on labor and materials over the past two years, as well as the effects of demand surge, but excludes the impacts of excessive litigation, fraudulent assignment of benefits and social inflation.

During the CoreLogic webinar, Smith addressed an audience question about demand surge, confirming that the estimates from the analytics and data-enabled solution provider do not currently include an provision for demand surge. “My anticipation is that the demand surge [will] not be particularly notable, one reason being that we’re not far from some fairly major metros that have a lot of capacity in terms of materials and labor.” While some damaged areas lie beyond a typical commute range, “there is a lot of regional capacity that is not too far away in the state of Florida that hasn’t been hit that hard from the event. So, we wouldn’t expect demand surge or the post-loss amplification per se to be that overwhelming.”

Asked how reconstruction cost inflation factors incorporated in CoreLogic’s Ian loss estimate compare to inflation factors for 2021 and 2020, Smith said reconstruction cost values, which are key building blocks of CoreLogic’s loss estimates, evolved quickly during the pandemic. “There were some large increases in 2020 and 2021. [More recently], there have been drops in some of the inputs in lumber prices and so on so that a lot of that raw inflation of RCVs has come down.”

Asked specifically how supply chain issues may create further challenges for recovery efforts, and about the potential for bad actors to take advantage of the situation, Brandon Burton, senior principal, Industry Relations, said that in this event, as in any storm event, early days of recovery will be the most difficult. “In this particular case, because of sheer amount of wind damage…there are very, very specific services [disrupted], supplies and even infrastructure damage that contractors are going to be dealing with. The ability to even do…a basic board up [is] going to be challenged—and not only because [securing] the supplies [is] a challenge, but just getting the resources into the area to perform the work is going to be a challenge.”

“It will improve over time. That’s what happens in these events…As each day passes and more infrastructure is brought online and more roads and areas are opened for transport, as bridges and island access are re-established, these things will slowly but surely take a foothold,” he said, referring to the initial mitigation phases of reconstruction and going on to describe the specific supplies and contractor skillsets needed for full restoration phases.

The possibility of bad actors in the contracting world is a definite risk at the outset of virtually every major contractor event, he said, noting, however, that some bad work is unintentional, arising from the fact that some contractors are just ill-prepared to take on work of post-storm reconstruction.

Earlier in the session, Burton had revealed that 30 percent of established contractor businesses that have responded for the first time to a hurricane event in the past are out of business within the next 12 months because of lack of preparation. “They are not prepared to withstand financing the work that is being performed in an area like this, and then financing the collection of those monies from an unfamiliar market with unfamiliar clients.”

George Gallagher, a principal account executive for CoreLogic, responded to a question about the need for experienced out-of-state property inspectors and appraisers to help FEMA respond to Hurricane Ian in Florida, suggesting instead that such professionals should contact banks and insurance companies, who are likely to have a high demand for such services.

During the webinar, CoreLogic also confirmed that its estimates do include water losses paid under wind policies, using leakage amounts from prior events as a guide. In a media statement, Verisk said that “storm surge leakage losses paid on wind-only policies due to government intervention” is excluded from its estimates, as are losses to uninsured properties infrastructure losses, environmental cleanup costs and boat losses covered under inland marine policies. In a writeup on the the Verisk blog, the firm said that storm surge losses quoted in the industry loss estimate are reflective of 5 percent leakage assumptions on wind-only policies for residential, renters, manufactured homes, small commercial, industrial, commercial residential risks, and 100 percent coverage on larger commercial, industrial and commercial residential risks.

More Damage to Auto Insurer Profits

The S&P Global Ratings report noted that while the bulk of Ian’s losses will be residential property losses, commercial property losses will also be substantial. Unlike homeowners policies, commercial property insurance policies cover flood risk, adding to losses on the commercial side.

The S&P report also highlighted reasons for uncertainty for forecasters trying to project personal auto insurance losses, noting that while extensive flooding from Ian suggests that carriers will experience material auto physical damage losses, mandatory evacuations of some storm zones could have reduced the impact.

Separately, another unit of S&P, S&P Global Market Intelligence, offered some analysis of auto insurance losses. Tim Zawacki, principal insurance analyst, S&P Global Market Intelligence, reported that flooding during Hurricane Harvey in Texas in 2017 added 2.5 points to the nationwide personal and commercial auto physical damage loss ratios.

Since Harvey stalled over Houston, which is much larger than the Cape Coral-Fort Myers and Naples-Marco Island areas impacted by Ian in Florida, Zawacki’s report suggests 2.5 points is an unlikely upper bound for the financial damage that Ian will add to auto insurers’ underwriting ratios.

According to Zawacki, S&P’s latest projection of net premiums earned for auto physical damage indicated that it would take more than $1.1 billion in incurred losses to add a full point to the prospective loss ratio.

But the report also delivers the bad news that the industrywide private passenger auto physical damage combined ratio is poised to rise to a 25-year-plus high when the books on 2022 are closed, with an 81.9 second-quarter incurred loss ratio contributing to that record.

“The personal and commercial auto physical damage lines, which have been under significant pressure on a nationwide basis for the past 15 months amid rampant inflation in vehicle repair and replacement costs, could experience an influx of flooded vehicle claims,” Zawacki said.

As part of his analysis, Zawacki contrasts more than $2 billion in Texas personal auto incurred losses from Harvey, and $380 million in personal auto physical damage losses in Florida from Charley.

Still, even a Charley-like figure would damage auto underwriting results for the state of Florida, the report says, noting that an inflation-adjusted 2004 value would have added 9.3 points to Florida’s auto physical damage loss ratio for 2021.

Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook

Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook  Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages

Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages  RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit

RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit  Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash

Retired NASCAR Driver Greg Biffle Wasn’t Piloting Plane Before Deadly Crash