Josh Waldrum knows from firsthand experience that most of the folks who drive for rideshare services like Uber and Lyft are not well informed about the insurance issues that insurance professionals see as problematic, such as coverage gaps and the amounts and types of coverage needed.

Josh Waldrum knows from firsthand experience that most of the folks who drive for rideshare services like Uber and Lyft are not well informed about the insurance issues that insurance professionals see as problematic, such as coverage gaps and the amounts and types of coverage needed.

Waldrum is the director of search engine optimization (SEO) at Austin, Texas-based The Zebra, a digital auto insurance agency and online auto insurance comparison site. As a member of his company’s marketing team, he took the challenge of foregoing driving his car for the month of January in favor of getting around exclusively through the services of rideshare companies Uber and Lyft. He wrote about the experience in a blog on his company’s website.

Asked why he did this, Waldrum said: “We talked about it a lot. It somehow just naturally came up. I think I first mentioned, ‘What if we found somebody to give up their car for an entire year and document all the stuff?’ That was way too much. Then, ‘I think a month could make sense. I could do this. It’s not that hard.’

“It came from that. I blindly signed up for it. When it actually came January I was like, ‘Oh man, what was I thinking?'” But he said all was well in the end.

In all, Waldrum took 50 rides during the month: 25 with Uber in the first half of January and 25 with Lyft in the last half.

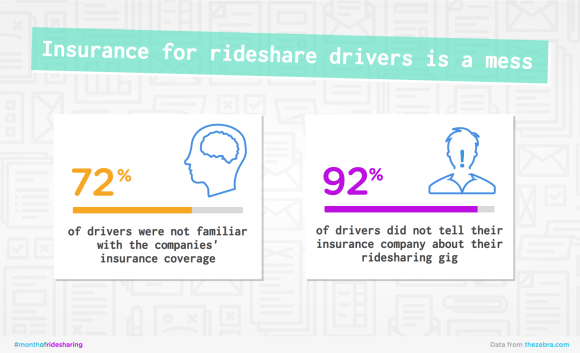

While his survey was in no way scientific, it was revealing. In conversations with drivers during his rideshare experiment, Waldrum found that a very large percentage of the drivers who work for these companies didn’t really know much about insurance requirements or about the coverage their respective companies provide. In addition, most didn’t tell their personal auto insurance companies that they were doing this.

Specifically, he found that 72 percent of the drivers he spoke with were not familiar with the coverage offered by Uber and Lyft, and 92 percent of the drivers had not told their own insurance companies that they were driving for these companies.

“Definitely all the drivers were an open book when I asked about this,” Waldrum said.

Waldrum said he believes companies like Uber and Lyft probably do communicate to their drivers about the insurance coverages the companies provide. But, he said, “I don’t think they do a good job of telling them the other piece of it, which is that their personal insurance company would want to know” that their insureds are driving other people around for a fee.

One of the main concerns of personal auto insurers has been the coverage gap between the time a driver is logged into the online rideshare service application as being available to pick up a customer and when a customer is actually in the vehicle.

Waldrum said the rideshare drivers he spoke with generally were confused about such coverage issues.

“I’d taken a lot of Uber before this whole experiment. Since I started working here I always found myself asking the drivers about insurance because I’m learning about it here and it was interesting,” Waldrum said.

“There was confusion all around the board. When I’d ask them, ‘How does Uber’s insurance work?’ or ‘How does Lyft’s insurance work?’ I got a lot of confused responses, where people really weren’t totally sure when they were covered and what was covered by Uber and Lyft,” he said.

Cheaper Rides

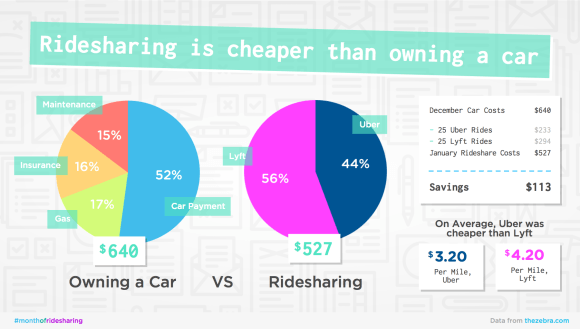

In his blog post, Waldrum said that factoring in the cost of car payments, gas, personal auto insurance and auto maintenance, ridesharing—at least for him for one month—was cheaper than driving his own car. Waldrum estimated his personal auto expenses for a month amounted to $640, while the cost of his 50 Uber/Lyft rides for the month of January came to $527.

He recognized that the results were subjective and that his commute to work was only 3.25 miles. A longer commute obviously would have translated into more expensive rides, as would a larger number of total rides taken.

He also acknowledged the limitations in exclusively using rideshare services versus driving one’s own vehicle. “After doing this experiment, I realized that having the flexibility to go anywhere at any point in my own car was something that’s hard to put a price tag on,” Waldrum wrote.

He said his experiences with both Uber and Lyft were “completely satisfying,” however. The average wait time for both was just over four minutes, and though he had expected he might have a harder time getting a ride in the morning when it was time to go to work, that did not occur.

Uber was somewhat cheaper than Lyft (Uber lowered its prices during the time of Waldrum’s experiment); the 25 rides with Lyft cost Waldrum $60 more than the 25 rides with Uber.

He found that more than half of the drivers he used (60 percent) drove for both Uber and Lyft and that there was a wide range in the age of the drivers—from college students to retirees.

The Insurance Challenge

Local communities, states and the insurance industry all are grappling with the issue of finding workable solutions that provide public protection while allowing for innovation and growth in new ventures like TNCs.

Legislation is pending in at least 35 states addressing the insurance challenges that TNCs present, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), which recently adopted a white paper on transportation insurance coverage issues in the sharing economy.

The NAIC’s paper, Transportation Network Company Insurance Principles for Legislators and Regulators, outlines insurance considerations to help state and local policymakers who are crafting TNC laws or regulations.

In the paper, the NAIC points out that “though the largest TNCs provide commercial coverage, those TNC’s policies may not provide the same uninsured/underinsured motorist (UM/UIM) coverage, medical payments coverage, comprehensive coverage or collision coverage that the drivers had purchased in their personal auto policies.”

The NAIC also acknowledged that many drivers are unaware that their personal auto policies have livery exclusions, under which coverage is disallowed for activities such as driving people around for a fee. Other TNC drivers may know about the exclusion but “simply hope for the best,” the NAIC said.

Some say the insurance industry has been slow to respond to the needs of the growing TNC industry with new products that address issues such as the coverage gap, but companies now are beginning to create new offerings for this industry.

In November 2014, Erie Insurance introduced rideshare coverage in Indiana and Illinois that provides coverage for every part of the trip—before, during and after the hired ride—by removing the “business use” exclusion in its policies, the company said.

In response to a new law in Colorado that requires rideshare drivers to have insurance for the “gap” period, in January Farmers Insurance created a rideshare coverage endorsement to meet that state’s mandate. Other companies like MetLife and USAA also have rolled out TNC products in Colorado.

In February, GEICO said it was launching a product that provides coverage both for personal and ridesharing use. The product is offered through GEICO Commercial at a price that is significantly lower than taxi and commercial rates, according to the company.

Modern Underwriting Technology: Decisive Steps to Successful Implementation

Modern Underwriting Technology: Decisive Steps to Successful Implementation  Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages

Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages  Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes

Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes  Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk