Insured losses in the first half of 2014 were $17 billion, considerably below the $25 billion average over the past 10 years, according to Munich Re’s 2014 Half-Year Natural Catastrophe Review.

Overall economic losses were also lower than average, at $42 billion in first-half 2014 compared to the 10-year average of $95 billion.

There were 2,700 deaths as a result of natural catastrophes in the first six months compared to the 10-year average of 53,000. Munich Re counted approximately 490 loss-relevant natural catastrophes.

Torsten Jeworrek, Munich Re’s board member responsible for global reinsurance business, said that while the relatively mild natural catastrophes so far this year are good news, “we should not forget that there has been no change in the overall risk situation. Loss minimization measures must remain at the forefront of our considerations. They make absolute sense from a macroeconomic perspective, as lower subsequent losses mean that they mostly generate savings of several times the investment amount. And they protect human lives.”

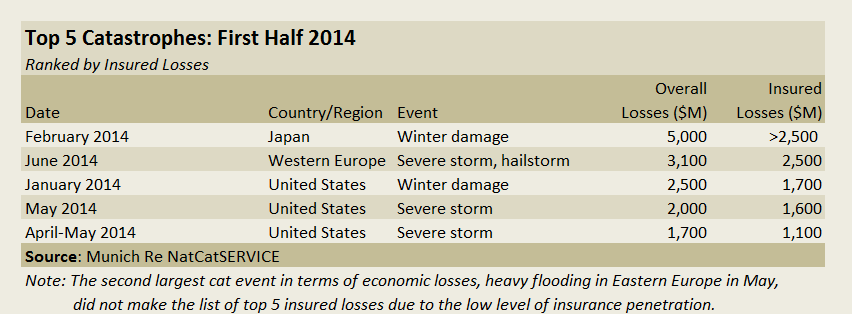

The most costly natural catastrophe worldwide in the first half was a pair of snowstorms that hit Japan in February, causing overall losses of around $5 billion and insured losses of more than $2.5 billion.

Extremely cold temperatures and heavy snowfall also caused significant losses in the U.S. and Canada, totaling approximately $3.4 billion. The most costly storm, during the first week of January, produced $2.5 billion of economic losses, and $1.7 billion in insured losses—making it the third costliest cat of the period in terms of both economic and insured losses.

Extremely cold temperatures and heavy snowfall also caused significant losses in the U.S. and Canada, totaling approximately $3.4 billion. The most costly storm, during the first week of January, produced $2.5 billion of economic losses, and $1.7 billion in insured losses—making it the third costliest cat of the period in terms of both economic and insured losses.

The harsh winter had a heavy impact on U.S. business, as many companies were forced to stop production. A snowstorm at the end of January brought the Atlanta metropolitan area almost to a standstill due to a lack of snow-clearing equipment for a city unused to such conditions.

“The harsh winter in the Midwest and on the East Coast once again exposed the vulnerability of infrastructure in the U.S.,” said Tony Kuczinski, CEO and president of Munich Re America. “Our industry and government must work together to encourage and facilitate greater investment in infrastructure projects that protect communities from loss. Consumers must be informed about the natural catastrophes they are exposed to; what they are or are not insured for; and how to protect their homes and businesses to withstand locally occurring natural hazards.”

Peter Höppe, Head of Munich Re’s Geo Risks Research Department, noted a link between the weather extremes in the northern hemisphere this winter—“significant and lengthy meanders in the jet stream.” These also explain an extraordinarily mild winter across large parts of Europe, Höppe said, noting the ongoing scientific debates over whether sustained changes in jet stream patterns might increase in the future due to climate change.

In Europe, a mild winter contributed to heavy flooding in England that lasted into February, causing overall losses of $1.3 billion and insured losses of $1.1 billion.

A June 9 storm front in Germany brought localized heavy damage caused by wind squalls and hailstones, causing overall losses of around $1.2 billion, with $890 million insured. The front also passed through France and Belgium. Overall losses in the various countries amounted to $3.1 billion, of which $2.5 billion was insured.

Hurricane Arthur, the first named storm of this year’s Atlantic hurricane season, made landfall July 4 on North Carolina’s barrier islands as a category 2 hurricane with wind speeds reported up to 100 mph. While the storm did not affect the U.S. mainland dramatically, “Arthur showed that nobody should think that risks have vanished only because the recent hurricane seasons were comparatively calm. The risk has not changed, and it remains important to invest in improving the resilience of buildings and infrastructure, in order to reduce losses and the loss of lives caused by such events,” Höppe said in a statement.

Höppe expects ENSO, a naturally occurring phenomenon that involves fluctuating ocean temperatures in the equatorial Pacific, to impact weather events for the remainder of the year. “With the contrary effects of El Niño and La Niña, ENSO can influence weather patterns in many parts of the world,” he said. “It currently looks as though a moderate El Niño will develop by the autumn, with warm water from the South Pacific moving from west to east, thus shifting wind systems and precipitation across the Pacific basin.”

Hurricane activity in the northern Atlantic normally decreases during El Niño phases, Munich Re said, while the number of typhoons in the northwest Pacific usually increases (though they make landfall more rarely). And the stronger the El Niño, the more likely it is that there will be a La Niña in the following year, when hurricane activity tends to increase.

20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut

20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut  Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality  Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook

Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook  Preparing for an AI Native Future

Preparing for an AI Native Future