Commercial insurance pricing is cyclical, and the top of the hard market cycle appears to be at hand. While traditional cycle models point the finger at the availability of capital and the basic rules of supply and demand, this is only one driver.

Executive Summary

During the period 2013 through 2018, the U.S. did not become less litigious nor did Atlantic sea surface temperatures get less warm. Yet rates for U.S. excess liability and Atlantic hurricane both reduced, observe the co-founders of UWX. Here, they describe the human factors driving cyclical behavior.Even more impactful are the human factors at work, as the market well knows. The cycle has its own logic and is much more rooted in herd mentality—group behaviors grounded in a need to belong and be recognized.

These behaviors can and should be spotted, tracked and actively managed. They affect management as well as underwriters and are evidenced, for example, by insurers and reinsurers all looking to grow or cut back at the same time.

The cycle will turn, and the unprepared will get swept along. To quote Boris Johnson, the former British prime minister: “When the herd moves, it moves.” (Editor’s Note: Johnson said this during a speech in 2022 to announce his resignation as prime minister.)

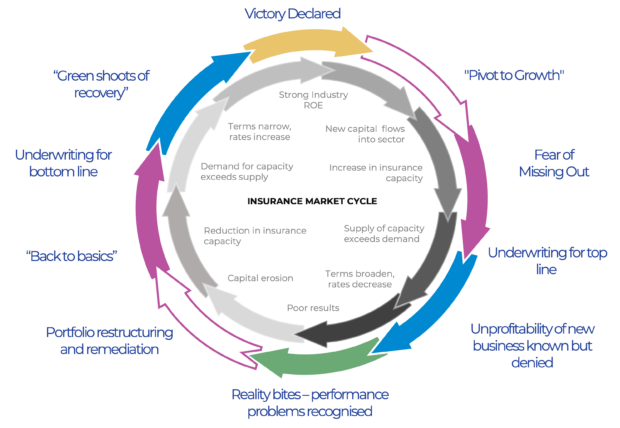

Drawing on research conducted in conjunction with SBS Swiss Business School and the International Association of Engineering Insurers (IMIA), UWX has mapped out the behaviors that are associated with different phases of the cycle. Schematically, this behavior cycle is represented below.

Viewed in this way, the market cycle is both driven and informed by human behavior.

When results are good, insurers are confident. They “pivot to growth,” assuming they can scale their businesses without compromising on underwriting performance. This soon translates into “fear of missing out” with all insurers fighting to grow at the same time.

Premium targets balloon with the result that underwriters are tasked to produce, rather than underwrite. Underwriters recognize that terms are softening and becoming unprofitable but are motivated to meet the premium targets they have been set. Ever more compromises are made, and underwriters start to accept whatever terms they are offered.

Eventually “reality bites” and the unprofitability of particular portfolios no longer can be ignored.

Managers see these as specific problems requiring specific remediation. However, this focus on specifics becomes untenable as adverse development emerges across the broader portfolio.

This is when management demands fundamental change and orders the company to go “back to basics.” The focus shifts to the bottom line, with underperforming lines—and teams—culled. Market communication emphasizes discipline. Brokers are forced to narrow terms and increase prices to secure capacity and management points to improved technical pricing and other “green shoots of recovery.”

Encouraged, management maintains its emphasis on underwriting rigor. Profitability improves across the market and management teams celebrate their “victory” in turning around their portfolio. This sense of achievement instills management confidence, and the behavior cycle starts again.

UWX research and analysis has shown how behavior and communication change over the cycle. In the next couple of years, for example, current behavior and communication would suggest that the strategic focus for many insurers and reinsurers will shift more explicitly to premium production, also known as “underwriting for top line.”

To accommodate this, we are likely to see other behavioral tells. There will be pressure on underwriting managers to broaden internal guidelines and appetite. There also will likely be a focus on “optimizing” reserving practices so that they are less conservative.

It is important to recognize that “real world risk” does not drive the behavior cycle. For example, during the period 2013 through 2018, the U.S. did not become less litigious, Atlantic sea surface temperatures less warm, nor global terrorism less of a threat, yet rates for U.S. excess liability, North Atlantic hurricane and terror all reduced, at times dramatically.

“‘Real world risk’ does not drive the behavior cycle.”

The pattern is repeating now with leading industry figures decrying the illogical nature of it all. The warnings last year from Patrick Tiernan, Lloyd’s chief of markets, about reckless softening in the directors and officers market are just one example. (Q3 Market Message – Lloyd’s (lloyds.com) at 4.49 minutes)

But these warnings were not new. Note the message below from former Chief Executive Inga Beale and former Chair John Nelson in 2016 before the nadir of the market in 2017/2018.

“Current year underwriting is not profitable in the aggregate at the moment … this is a matter of great concern to us.”

John Nelson and Inga Beale, quoted in Insurance Journal, Dec. 13, 2016

‘When the Herd Moves, It Moves’

Even the most senior market figures appear incapable of stopping it, but this should not spell surrender. Best-in-class insurers and reinsurers recognize herd behavior for what it is. They know if they can accurately assess where they are in the behavior cycle, they can anticipate the likely next actions of the herd. And then they can plan and act accordingly.

In the next article in this two-part series, UWX focuses on how to measure behavior and how improved technology and technique are opening up a new world of performance metrics and management practice.

***

This article is based on research conducted by UWX AG, the commercial underwriting-focused consulting firm based in Switzerland, which was co-founded by Tony Buckle and John Carolin, CFA. Specifically, the article draws upon research Buckle conducted with the support of the International Association of Engineering Insurers (IMIA) for his doctoral dissertation at SBS Swiss Business School, and by Carolin, along with the support of Amazon Web Services. As part of the research, they interviewed underwriting officers, underwriting managers and senior underwriters in engineering and construction, including the CUO referenced in a sidebar to this article.

In the second part of a two-part series, the authors will explain how to measure underwriting behavior.

Related articles:

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality  Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages

Berkshire-owned Utility Urges Oregon Appeals Court to Limit Wildfire Damages  Nearly 26.2M Workers Are Expected to Miss Work on Super Bowl Monday

Nearly 26.2M Workers Are Expected to Miss Work on Super Bowl Monday  Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid

Beazley Agrees to Zurich’s Sweetened £8 Billion Takeover Bid