Over the last two years, insurers have been dealing with the most disrupted property reinsurance market since 1992.

As was the case in the post-Andrew era, reinsurers have abruptly hiked coverage costs, constrained capacity and limited cover by requiring higher retentions. Major reinsurers are pulling out of markets while insurers are pulling back from states like Florida and California.

Executive Summary

Traditional reinsurance capacity is shrinking relative to increasing risk, and a new risk transfer product—the modeled loss transaction—is providing additional reinsurance protection to insurers. This article explains how these transactions work and the benefits to reinsurers and ILS investors as well as to ceding insurers.(Editor’s Note: One of the co-authors, Resolute Global, announced the launch of “Footprint,” an MLT, which Resolute Global created in collaboration with global reinsurance broker Gallagher Re and catastrophe modeling firm Karen Clark & Co., a firm led by the second co-author, in April 2023.)

Both now and then, systemic underestimation of risk is largely to blame.

Reinsurers now rely on catastrophe models to assess risk, and for the past 30 years, the focus has been on “tail” risks and probable maximum losses (PMLs). But the current disruption in the market has not been caused by an unexpected mega-event resulting in losses well above market expectations. Rather it’s been caused, in large part, by the unexpected frequency of smaller losses from the so-called secondary perils.

The catastrophe models that have been used most heavily by brokers and reinsurers were designed to capture the large loss potential from infrequent, high-severity events like hurricanes and earthquakes, and it’s been well publicized these models have failed to accurately assess the loss potential from the frequency (aka, secondary) perils like wildfires, winter storms and severe convective storms (SCS).

The frequency perils are more impactful at the lower return periods of the exceedance probability (EP) curves, and this is where the legacy models miss. It may seem counterintuitive, but the frequency perils are more challenging to model due to their amorphous and dynamic nature.

Other pressures on the higher-probability, lower-return-period losses include rising construction costs, shifting demographics, social inflation and climate change. Climate change, in particular, is disproportionately increasing the chances of $20 billion, $30 billion and $40 billion losses from hurricanes as well as from the frequency perils.

As these factors continue to increase the risk and therefore the demand for reinsurance protection, reinsurers have two choices. They can continue to restrict coverage and withdraw from markets, or embrace new models and technology and expand business opportunities with innovative risk transfer products.

Industry leaders who recognize growing risk can be an opportunity rather than a threat are choosing the latter, and one such innovation is the “modeled loss” transaction.

The Modeled Loss Transaction

There’s an important underwriting adage: There’s no such thing as a bad risk, only a bad price. Reinsurers are pulling back from areas where they don’t have the right tools to confidently price the risk. Reinsurers in retreat are concerned the losses they’re paying out on reinsurance contracts are not being captured by the models they use to price those contracts.

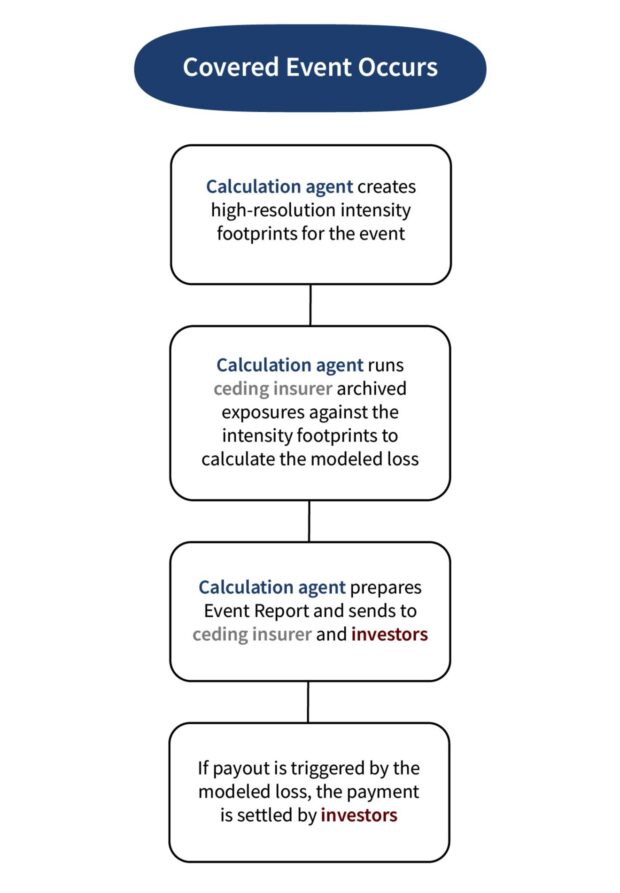

The new Modeled Loss Transaction (MLT) solves this problem. In an MLT, the payout is based on the modeled loss rather than the actual loss of the ceding insurer. The MLT relies on a calculation agent, typically the catastrophe modeler, to produce pre-event loss analytics and to model actual event losses as they occur.

To determine the modeled loss, the calculation agent runs a predetermined and archived database of policies and exposures through the model. MLTs also have been referred to as the “footprint” product because in order to estimate the loss, the first step is to produce high-resolution intensity footprints for the event. For example, high-resolution wind and storm surge footprints are required for a hurricane, and hail and tornado/wind footprints are required for an SCS event.

MLTs also can incorporate any agreed upon assumptions. For example, the ceding insurer may want to apply a factor to account for excess litigation in Florida or a specific demand surge function. These assumptions can be reflected both in the modeled EP curves used for pricing the transaction and in the modeled loss for a covered event.

This means there is complete symmetry between the transaction payout and the price, eliminating unpleasant surprises to reinsurers and ILS investors caused by loss inflation and model miss.

For providers of protection, the MLT solves many of the problems causing the current market disruption, including non-modeled or poorly modeled risks. Perhaps the most significant benefit of MLTs to reinsurers and ILS investors is the speed of settlement. It can take months or even years for the actual claims from large loss events to fully develop and settle.

These long settlement times on indemnity contracts provide opportunities for loss creep and result in trapped capital, which limits flexibility, investment opportunities and returns. Uncertainty about the ultimate loss and subsequent tied-up capital is one of the biggest challenges investors have experienced with indemnity contracts.

Conversely, new high-precision models can accurately estimate the losses from actual events within days of occurrence such that an MLT can easily settle within 30 days. This rapid settlement provides quick liquidity to ceding insurers and eliminates the risk of adverse development as well as trapped capital for reinsurers and investors.

While there’s little downside to reinsurers and ILS investors, the ceding insurer has to be confident the model used for an MLT can accurately estimate its indemnity losses for real events when they occur. Otherwise, there would be too much basis risk, and the transaction wouldn’t be viable. The model underlying an MLT must demonstrate skill in reproducing the insurer’s actual claims and losses over a large enough set of historical events.

In order to test the skill of a model, an insurer should be able to download high-resolution intensity footprints into the model along with its own contemporaneous exposure data to test how well the model estimates actual claims and losses for each historical event, ideally going back at least 10 years. For most perils, this should provide a sufficient basis risk analysis.

Options for Cedents

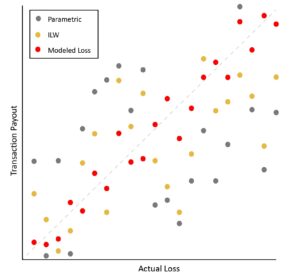

Indemnity covers provide the ideal protection for ceding insurers; however, it can be prohibitively expensive to purchase as much cover as the ceding insurer would like. Currently ceding insurers can use supplemental, lower-priced coverage such as parametric (payment triggered by a specific metric such as windspeed) and ILW (payment based on industry loss versus insurer-specific loss) transactions, but these come with their own drawbacks.

Parametric triggers, for example, are most suitable for companies with one large facility or a highly concentrated book of business. Conversely, for insurance companies with diversified books, by line of business or geography, the basis risk can be very large with a parametric product.

ILWs carry with them two levels of basis risk for the ceding insurer—there can be inaccuracy in the estimated industry loss, and an event can cause damage in areas where the ceding insurer losses are not highly correlated with the industry. ILWs do not solve for reinsurer and investor challenges including adverse development and trapped capital.

New high-precision models are able to accurately estimate the losses from actual events soon after they occur, thereby reducing both basis risk and settlement times on the transactions.

Structuring the Transaction

The first MLTs have covered the SCS peril, underscoring the MLT’s ability to address the frequency perils that traditional reinsurers now want to avoid.

While a single SCS event is not likely to result in a solvency-impairing loss for most insurers, the accumulation of many small to moderate-size losses can result in multiple hits to retentions and negatively impact financial results. An MLT can be structured to protect retentions as well as large losses from major events.

MLTs offer complete flexibility with respect to transaction design. Even annual aggregate covers—essentially non-existent in the traditional market for the past several years—are being offered to insurers on a modeled loss basis. The fact that the pricing can be completely aligned with the payout makes even annual aggregate transactions interesting to investors.

MLTs can cover any type of modeled peril, including hurricanes, earthquakes, winter storms and wildfires. And they can be used for insurer-specific portfolios or the industry as a whole in ILW contracts.

As reinsurance supply struggles to meet growing demand, the MLT offers a solution. High-precision modeling paired with the MLT structure enables reinsurers to expand capacity with confidence, and by attracting new capital, the MLT can ease tight conditions and help the industry remain resilient and relevant in a world of ever-increasing risk.

Rather than retreat in the face of escalating risk, insurers and reinsurers equipped with high-precision models and innovative structures for risk transfer can turn the threats of growing loss potential into opportunity. Similarly, MLTs allow investors to benefit from non-correlated returns and capitalize on attractive market conditions without the challenges of traditional products.

Preparing for an AI Native Future

Preparing for an AI Native Future  How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll

How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll  RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit

RLI Inks 30th Straight Full-Year Underwriting Profit  Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk