Workers compensation has been a profit juggernaut for the property/casualty insurance industry over the past several years.

Underwriting profits from the workers comp line have accounted for the entirety of the industry’s profits from underwriting over the past decade. If those profits begin to dry up, many companies will feel it.

Executive Summary

The majority of excess or unnecessary opioid prescribing appears to have been wrung from the workers compensation system, analysts at Assured Research have found, based on an analysis of data from a series of reports from the Workers Compensation Research Institute and industry loss trends. Here, Assured Research President William Wilt reveals the impact that changing prescribing patterns has had on workers comp ratemaking and loss reserve adequacy, advising actuaries to carefully watch prescribing patterns going forward in order to avoid mismatches between their historical experience period and current practices.A version of this article was originally published in the October Assured Briefing for subscribers to Assured Research reports. The article is being republished by Carrier Management with permission from the author.

There are several worrying trends that could conspire to shrink workers comp underwriting margins going forward. Among them: a rising medical trend line; a narrowing gap between wage and medical inflation; and reserve redundancies (at nearly 15 percent of workers comp premiums in recent years) that will decline if the medical trend line continues to rise. We reviewed these possibilities in our September Assured Briefing.

Here, we turn attention to another trend that could push workers comp underwriting results in the wrong direction: changes in prescribing patterns for opioids in workers comp claims. A rapid deceleration in the frequency of opioid prescriptions during the years 2010-2018, and a similar sharp drop in the dosage intensity of opioid prescriptions during those years, is leveling off. While not the entire story, there’s little doubt that the precipitous decline in opioid prescriptions had a positive impact on workers comp results in recent years. Carriers and their actuaries need to be careful to analyze any stabilization—or reversal—of this key driver of past improvements in workers comp results as they develop loss cost projections into the future.

Our Findings Are Straightforward

Our analysis of opioid prescription frequency, projected vs. realized loss costs in recent years, and workers comp loss reserve adequacy lead us to a central conclusion: The claim benefits of the roughly decade-long effort to decrease the use of opioids in workers comp claims is now in the eighth inning or so.

That matters because research conducted by the California Workers Compensation Institute and the Workers Compensation Research Institute have found that the lost time and overall cost of claims with material opioid prescriptions are multiples higher than claims where opioids are either avoided or used in moderation. We note that these and other similar studies warrant careful citation of the parameters studied (e.g., as to measurements of opioid Rx, type of injury, lost time, claims costs, etc.), which we have omitted here. Still, the takeaways are clear and consistent across studies: Claims with opioid Rx cost materially more than claims without.

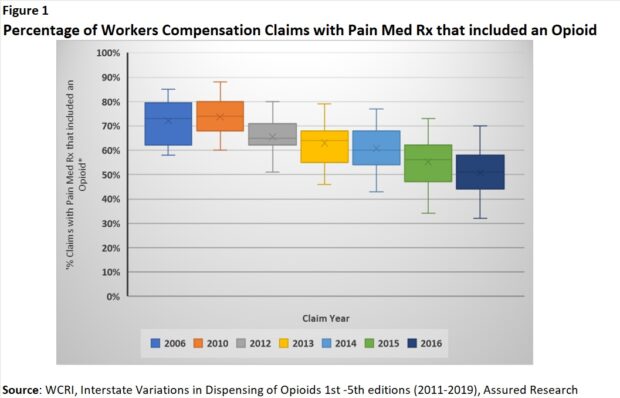

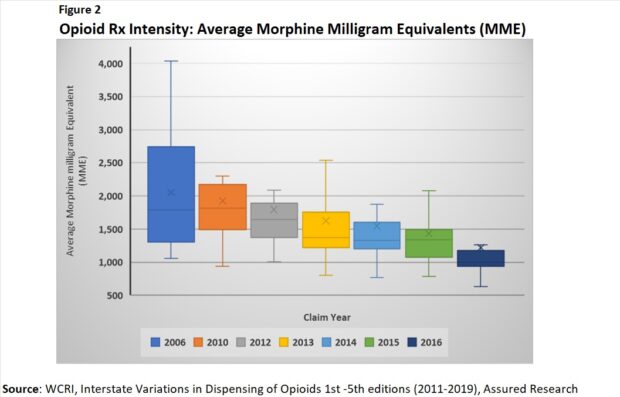

With thanks to the WCRI for the assistance in harnessing their many reports over the past decade, we extract WCRI data related to the frequency and intensity of opioid prescriptions below, supporting our conclusion. The data relate to opioid prescriptions in nonsurgical claims with at least seven days of lost time across 27 states. The content of the WCRI reports changed after their 2019 publication, so in the accompanying charts (Figures 1 and 2) we show the data from their first five reports, which allows us to track the interstate variability across the frequency and intensity of opioid prescription per lost time claim.

The frequency of opioid prescriptions in workers comp claims appears to have peaked in the late 2010s and decelerated sharply thereafter. (Figure 1)

The same observation applies to intensity, measured as morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/claim to create a consistent measure across different types of opioids. (Figure 2)

Data in subsequent WCRI reports show that the sharp deceleration began to level off around 2019 or so.

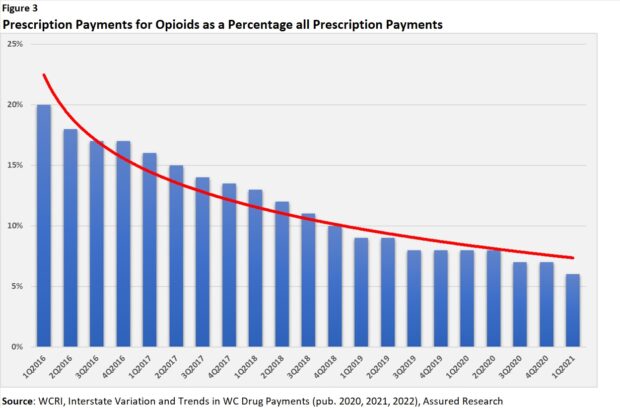

WCRI’s most recent reports (publication years 2020-2022) provide information on the overall payments for opioids as part of total workers comp payments for prescription drugs. While some information is lost from the earlier studies, it’s easy to see that opioid payments declined steadily from early 2016 into the early 2019 timeframe and then decelerated much more slowly thereafter. (Figure 3)

As opioids spending decreased, the spending on NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) increased, but only somewhat, along with agents applied topically.

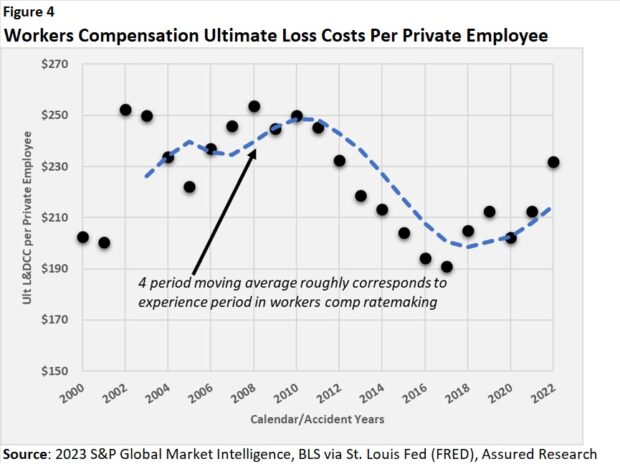

Turning to industry loss data for the workers comp line overall, we note a sharp deceleration in ultimate workers comp losses per private employee from accident year 2010 to 2017/2018. Like the earlier trends in opioid prescribing, the decline in workers comp losses/employee has halted. In fact, it looks to be reversing. (Figure 4)

Ahead of the reversal, there’s an insight about workers comp ratemaking during the 2011-2018 years that we can draw from the data. Recognizing that workers comp ratemaking uses a three- or four-year historical experience period to forecast needed premiums, our analysis of the data here suggests that loss costs forecasted for premium projections for those years were much higher than realized loss costs.

Helping the reader to follow our analysis, on the accompanying graph (Figure 4), the black dots represent ultimate loss costs per employee by year (losses include defense costs and containment expenses). The dotted blue line indicates the four-year moving average—a proxy for the four-year experience period used in workers comp ratemaking. (We made no adjustments for trends in indemnity or medical costs or exposures. Ours is a highly simplified example.) As costs inflected downward beginning in 2011, the forecasted loss experience overshot the realized losses through 2017, as evidenced by the dotted blue line being higher than the dots or realized costs.

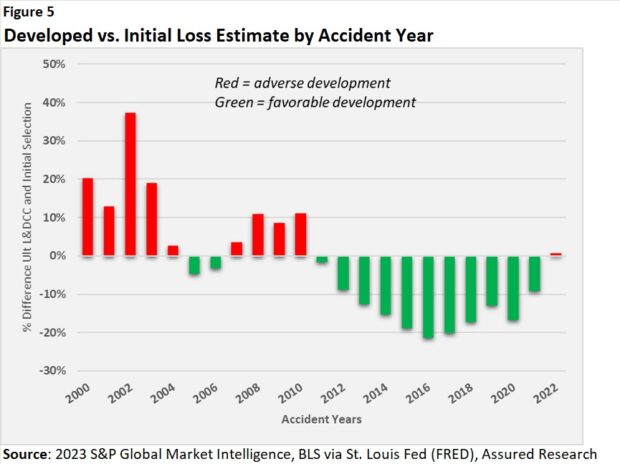

During those same years, not surprisingly, loss reserve redundancies accelerated. (Figure 5)

In fact, the ultimate workers comp loss estimates from the years 2011-2018 decreased by an average of around 15 percent from their initial estimate to their “final” estimate (where we’ve used projections from our year-end 2022 Reserve Study).

Putting It All Together

These trends fueled the “workers comp as earnings juggernaut” statement that opened this report, but the rub is that opioid prescribing appears to be reaching a resistance point or is at least no longer declining at anywhere near the pace it did during the 2010-2018 period.

To be clear, we don’t know where the resistance point might lie, but it appears the majority of the “excess” or unnecessary opioid prescription costs has been wrung from the system.

If opioid prescription patterns simply glide downward toward some natural resistance point (e.g., we assume some percentage of serious claims will involve the use of opioids), then, in theory, no major mismatches should arise between the experience periods used to set workers comp rates and the practices affecting current loss experience. Risks arise, however, from prescribing patterns that could become too conservative—and then reverse, even if only modestly—or if actuaries bake declining loss costs into a trend that fails to materialize when opioid prescribing reaches its nadir.

Professionals working in and around the workers compensation insurance industry deserve our thanks for their role in successfully reversing adverse opioid trends that developed during the early 2000s. The rapid deceleration in the frequency and intensity of opioid prescribing patterns surely had an outsized and positive impact on workers comp claim costs. Multiple studies have documented that between similar claims, the one with opioid prescriptions is likely to cost materially more than one without.

But based on this work, we’re inclined to think that the claim benefits from this megatrend is now winding down to an endgame—approaching the eighth inning or so.

What’s an Actuary to Do?

What if we’re right? Or wrong? Either way, it seems highly unlikely that the recent claims history of any insurer of workers compensation would be unaffected by the trends identified in this article. The situation calls out for a special study of the development patterns and trends of claims with opioid prescriptions separately from those without.

Practicing actuaries will surely be more inventive than we can prescribe in a few short sentences. But at baseline, we suspect any study would start by separating workers comp claims with and without an opioid prescription. Notably, WCRI studies cited throughout this article focused on nonsurgical claims with seven or more days of lost time. Perhaps separating nonsurgical from surgical claims would identify different prescribing behaviors and claim patterns.

Once the claims are separated, we’d recommend examining the development patterns and loss trend (per some exposure base—people or payroll). Actuarial mistakes might be avoided, for example, if the triangle of claims with an opioid prescription shows both decreases in losses/year (fewer opioid prescriptions) and shortening development patterns (as from, perhaps, lower intensity of opioid Rx and faster return-to-work among claimants).

Even if these separated triangles had to be glued back together (if one or both lacked credibility on their own, for instance) the actuary would better understand the underlying trends and could make more informed decisions about the likely behavior of claims in the years ahead.

And insofar as most workers comp insurers employ or contract with healthcare professionals to manage complex claims—talk to them! Surely much could be learned from conversations about prescribing patterns and when, or if, some natural resistance point in opioid prescribing might be reached.

How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll

How Americans Are Using AI at Work: Gallup Poll  Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs

Experts Say It’s Difficult to Tie AI to Layoffs  Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook

Execs, Risk Experts on Edge: Geopolitical Risks Top ‘Turbulent’ Outlook  AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage

AIG, Chubb Can’t Use ‘Bump-Up’ Provision in D&O Policy to Avoid Coverage