In their 1999 paean to California, the Red Hot Chili Peppers sang that “Destruction leads to a very rough road, but it also breeds creation.” The rock band was referring to earthquakes and tidal waves, but in the intervening years wildfires have been the destructive force in California, typified most tragically by the 2017 Camp Fire in Paradise that consumed nearly 19,000 structures and caused 85 fatalities.

Executive Summary

As carriers pull back insurance for new homes and businesses in the Golden State, property risk analytics tools are changing the understanding of wildfire damage risks.Here, insurance journalist Russ Banham talks to ZestyAI Co-Founders Attila Toth and Kumar Dhuvur about wildfire risk scores available from the InsurTech. Banham also gets an assessment of the wildfire risk exposure on his own California home—and advice from Toth about measures he can take to lower it.

The catastrophic risk of wildfires recently impelled two of the five largest insurers in the state to stop writing new property insurance policies for homeowners and businesses, and one of the top five to cap the number of policies it will write. Wildfire risks also have bred creation, evident in more innovative ways to understand wildfire property risks.

A case in point is ZestyAI, an InsurTech that uses aerial imagery and AI to model the vulnerability of structures on a building-by-building basis. By offering its data-driven insights to insurance carriers, the information can then be passed on to policyholders to reduce their homes’ vulnerability to fire damage and destruction. The mitigations may even create more competition in the fading insurance market, possibly reducing the high cost of insurance for many homeowners and businesses.

State Farm was the first carrier to announce in late-May that it had stopped accepting applications for property and casualty insurance, followed about a week later by Allstate. In July, Farmers put a cap on new policies. In their decisions, the insurers cited inflation, rising rebuilding costs, reinsurance capacity and rapidly rising catastrophe exposures. State Farm recently asked the California Department of Insurance to approve an average 28.1 percent increase in insurance rates for the homeowners it continues to insure; Allstate filed for a 39.6 percent increase.

In terms of rising wildfire exposures, the timing of the three carriers’ announcements was incongruous with recent events. From Dec. 31, 2022, through March 29, 2023, rainfall from a record 13 atmospheric rivers poured more than 78 trillion gallons of water on the state, turning arid landscapes across Southern California into picture postcards of Ireland. The prolonged drought that contributed to recent wildfires was declared over in all but 8.7 percent of the state. Reservoirs were filled to full or near capacity, and the snowpack in the Sierra Nevada was two to almost three times above average.

In April, electronic readings from 130 snow sensors placed throughout the state by California’s Department of Water Resources (DWR) indicated that the aggregate snowpack’s snow water equivalent was 61.1 inches (237 percent of average)—the highest statewide summary since 1952. Snow water equivalent is the amount of water in a snowpack and is a key component of DWR’s water supply.

Attila Toth, ZestyAI

All that moisture has reduced the prospect of wildfires to more historical averages. On Aug. 1, the National Interagency Fire Center projected that “significant fire potential” will be below normal at higher elevations and near normal elsewhere through the summer. The fire season in California progresses from July through October. As of Aug. 1, 3,880 wildfires were recorded by the state’s Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, but the destruction was limited to four properties.

It seemed counterintuitive that the three insurers had pulled back when potential property losses were lower. Insurance trade group representatives attribute their decision to Proposition 103. The 1988 consumer protection regulation prohibits insurers from using so-called “black box” computer models to predict future wildfire risks. Insurers maintain that the models are a way to factor climate change into their underwriting, but consumer advocacy groups claim the models’ opacity is a way for insurers to raise rates.

At a July 13 California Department of Insurance hearing, Consumer Watchdog stated that its assessment of private computer models indicated severe flaws. “Models are imprecise and often wildly inconsistent when projecting future insurance losses, [leading] to arbitrary and unfair rates and premiums for Californians.” The nonprofit organization proposed that the state develop a public model to predict wildfire risks to “prevent insurance price-gouging.”

Kumar Dhuvur, ZestyAI

Meanwhile, concern is growing that other insurers selling property insurance policies to homeowners and businesses may follow the lead of State Farm, Allstate and Farmers. Were this to occur, the volume of policyholders in the last-resort California FAIR Plan, which insures high-risk properties unable to buy insurance, will expand. In 2018, the FAIR Plan insured 126,000 properties; in 2022, the most recent year for publicly available records, the number of insured properties catapulted to 272,000. In a statement, the Fair Plan projected an “impending insurance unavailability crisis.”

All About the Structure

Against this grim backdrop, ZestyAI may offer a measure of hope. Since its founding in 2015, the company has racked up a veritable “who’s who” of major insurance clients in California, including Farmers, Berkshire Hathaway, Amica Mutual, Cincinnati Financial and even the California Fair Plan, “among many, many others,” said Co-Founder Attila Toth. “Our contract with many carriers precludes naming them.”

Toth confirmed that the extreme snow and rainfall in California have acutely reduced the risk of wildfire losses, but he said the accumulating vegetation since the beginning of the year will lead to significant losses once drought conditions return. Periodic droughts are common, occurring in 1918-1920, 1928-1935, 1947-1950, 1976-1977, 1987-1992, 2000-2002, 2007-2009, 2012-2016 and 2019-2023.

Lengthier droughts, as measured by the Palmer Drought Severity Index, are associated with the peaks in very large wildfires in the 1920s and recent years. The most recent periodic drought was the driest on record, due to a combination of hot temperatures and low rainfall. The conditions fueled exceptionally large, destructive and more frequent wildfires.

Insurers in California cannot control the effects of climate change that have built up over the decades, much less use black box models predicting the impact of climate change-fueled wildfires on property risks. But they can use AI-driven risk analytics to assess these exposures on a building-by-building basis. According to ZestyAI’s recently published 2023 Wildfire Season Report, “Simply estimating wildfire activity doesn’t offer a precise forecast of the potential damages [because] the number of fires started, regardless of cause, differs very little from year to year, and the extent of wildfire spread only varies slightly with both fuel and drought.”

What does drive wildfire losses for insurance companies? “The obvious and most significant factor is the loss of structures,” the report stated. As Toth put it, “By providing a risk-based score on a building’s unique wildfire risk exposures, the most accurate view of potential wildfire losses is available.”

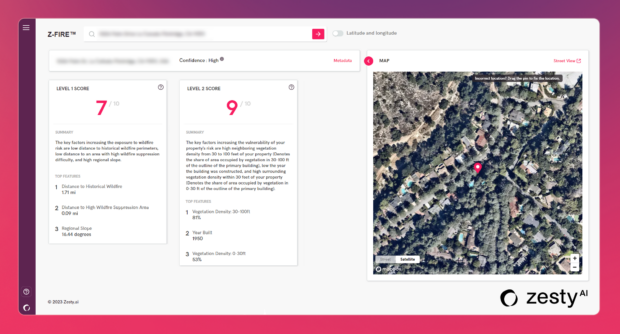

ZestyAI actually drums up two scores, dubbed Level 1 and Level 2, reflecting each structure’s wildfire risks. Both scores range from 1 to 10, with 10 being the highest risk. The Level 1 score is based on the likelihood of a property to be in a wildfire event. The information is drawn from historical fires in proximity to the structure, the level of the slope a structure sits on (the flatter the better) and challenges related to area wildfire suppression, i.e., the relative difficulty of performing fire control work, such as access to fire hydrants and local fire response teams.

Level 2 considers vegetation density within 30-100 feet of the outline of a structure, high surrounding vegetation within 0-30 feet of the outline of the structure and the year the building was constructed. ZestyAI’s carrier customers include the scores in their underwriting criteria and can pass on the information to agents and brokers to recommend risk mitigation actions to policyholders.

“You can’t do much about the distance of your home to historical fires, the slope of the parcel or anything else that makes wildfire suppression difficult, but you and your neighbors can change the vegetation density around your homes,” said Toth. “If you do three things—reduce the closeness of vegetation to the roofline, reduce the proximity of vegetation to the sides of the house and upgrade the vents to be ember-resistant—the score can drop from a nine to a six or even a five.”

Digging Into the Data

Toth was born in the small town of Zalaegerszeg, Hungary, a satellite state of the Soviet Union at the time. As a boy, he habitually asked questions in school that did not sit well with his teachers. “I’d ask, ‘Why is the world this way or that way?’ and they’d tell me to stop asking questions,” he said. “After the Berlin Wall came down, I decided to expand my purview from my close-minded upbringing and came to the U.S. in the mid-1990s. I wanted to discover new things.”

Chief among his discoveries was the nascent field of artificial intelligence. After receiving an MBA from Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, Toth became a strategy advisor at McKinsey & Company. There he met Kumar Dhuvur, who received his MBA from The Wharton School. “We began to explore AI once we learned about it, not knowing it would become what the Internet had become for business,” he said.

Having amassed significant knowledge and experience in AI, data analytics and risk management, the two friends founded ZestyAI as an AI-powered property risk analytics platform. “We endeavored to understand the most important drivers that caused one property to be more vulnerable to a wildfire than other properties in the same area,” Dhuvur said.

Using satellite imagery, the founders investigated all the wildfire events occurring in North America over the past 20 years. “We learned that when a wildfire impacts an area, not all properties are impacted; the historical rate of destruction is about 30 percent, meaning that 70 percent escape destruction,” said Dhuvur. “This is not a random occurrence.”

As they dug further into the satellite data to compare damaged structures to those that escaped destruction, factors like the slope of the land appeared to play a deciding role. “When wildfires spread, they spread uphill because of the embers, whereas a flatter terrain limits the spreading,” he explained.

Armed with this data, Toth and Dhuvur modeled the different factors using gradient boosting, a machine learning technique (machine learning is a subset of AI). “The best way to think of gradient boosting is as a series of conditional statements, such as, ‘If the property is on a slope’ and ‘If the property has a lot of vegetation,’ and other ‘If’ statements; the model then figures out which conditional statement is more important than the others,” said Dhuvur. “If the structure is on a significant slope, for example, then the vegetation cover matters less. If it’s not on a slope, then the vegetation matters more.”

The ability to evaluate the various factors scored by ZestyAI has increased since its founding eight years ago due to higher resolution imagery. “We began with satellite images only but have since partnered with special purpose aircraft companies to fly over every part of California two to three times a year,” said Toth, noting that the planes fly at low altitudes to collect images using high-resolution optics. Low-flying planes offer the highest-resolution imagery, he added.

The company also continues to rely on satellite imagery, including images regularly sent by providers that have launched large constellations of micro-satellites. “There’s been exceptional improvements in resolution quality and almost ubiquitous coverage,” he said. “When Kumar and I started the company, our first data feed (of pixels) was a resolution of 3-feet-by-3 feet, then 1-foot-by-1 foot, then 3-inch-by-3-inch, and now it’s down to 2-inch-by-2-inch.”

Risk Mitigations

I just happen to live with my wife and daughter in La Cañada Flintridge, a leafy suburb in Los Angeles County in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. The risk of a wildfire here is high, forcing us and many of our neighbors into the California FAIR Plan. Since the FAIR Plan is a customer of ZestyAI, I asked Toth if ZestyAI had scored our house. He turned to his computer and within seconds replied affirmatively.

The information was concerning: The Level 1 score was 7 out of 10, and the Level 2 score was 9 out of 10. Factors supporting the Level 1 score included a 1.7-mile distance to a historical wildfire, a 0.09-mile distance to a High Wildfire Suppression Area and, worst of all, a slope of 16.44 degrees. The Level 2 score factored the year in which the house was built (1950), high vegetation density within 30-100 feet of the outline of the house and high surrounding vegetation within 0-30 feet of the outline of the house.

Toth shared a birds-eye image of our house and the homes of our neighbors, which was taken by a low-flying plane in May. The structures underneath the trees are barely visible. Not that I was surprised: La Cañada Flintridge is one of 3,400 Tree Cities USA. Towering cedars and oaks canopy the area, making it a much-desired place to live. Residents have included Kevin Costner, Vince Vaughn, Angela Bassett, Ron Howard and Miley Cyrus. The median price of a house is $2.4 million, with some estates priced at $10 million and more. Our residence is at the other end of the median price range.

Toth advised that we and our neighbors trim the lower branches of trees and remove small shrubs close to our houses. He also provided some good news: The fire station within a mile of our house is certified in fire prevention and suppression techniques. “Go visit the station and ask if they can come by the house to offer some additional advice,” he said.

The day before writing the article, the annual bill from the California Fair Plan arrived. It showed a 10 percent increase in the premium, presently a whopping $3,693. I texted our independent insurance agent and mentioned the risk mitigations Toth recommended, asking if we would receive a premium discount once they were performed. She replied, “Those are good maintenance things to do, just for the general upkeep and prevention, but there are no further discounts for it.”

Our agent added, “All our carriers including the FAIR Plan have taken increases, and many carriers have pulled out of CA, which has tightened the market even more. I would definitely pay the coverage you have and keep it, as this is the best value and best coverage.”

It is what it is. We’re doing what Toth advised. In June, the Climate Prediction Center noted the beginnings of El Niño conditions, which typically results in colder winters and abundant rainfall. A greater than 90 percent chance that El Niño will last through early 2024 could mean another year of heavy rainfall in Southern California, local media has declared.

One week after the devastating wildfire that destroyed much of Lahaina in West Maui, the prediction was paradoxically fulfilled. In 24 hours on August 20 and 21, Tropical Storm Hilary delivered another four inches of rain to La Cañada Flintridge and area foothills.

Like other stalwart Angelenos, we have no plans to move. As the climate continues to change and confound, geography makes little difference. We are all vulnerable.

***

This article is featured in Carrier Management’s third-quarter magazine.

Related articles include:

- Are Winds of Change Blowing on California Insurance Law?

- A Community-Based Solution: How Actuaries and Fire Chiefs Can Tackle WUI Risk Together

- Grid-by-Grid: How One Tech Firm Dissects California Wildfire Risk to Sell Insurance and Reinsurance

All of the articles in the magazine are available on the magazine page of our website. Click the “Download Magazine” button for a free PDF of the entire magazine.

To be able to read and share individual articles more easily, consider becoming a Carrier Management member to unlock everything.

Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes

Insurance Groundhogs Warming Up to Market Changes  Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb

Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb  Chubb CEO Greenberg on Personal Insurance Affordability and Data Centers

Chubb CEO Greenberg on Personal Insurance Affordability and Data Centers  Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster

Lessons From 25 Years Leading Accident & Health at Crum & Forster