The highly thought-of share-and-share-alike attitude considered a virtue by some has become fighting words between ridesharing companies and the insurance industry.

“We try not to make it a battle,” said Robert Passmore, senior director of personal lines for the Property Casualty Insurers Association of America.

Steering away from giving a winner-loser perspective, he added: “We’re not against anybody’s business model.”

But it is a battle, and it’s unfolding state-by-state cross the country as PCI along with a handful of other powerful insurance groups spend considerable time and resources to make sure personal automobile insurance isn’t footing the bill for ridesharing activities.

The idea of ridesharing has taken off and propelled transportation network companies like Uber, Lyft and Sidecar into an emerging billion-dollar transportation market that local and state governments must now figure out how to deal with.

To regulate or not to regulate? That’s merely a starter question for these entities.

Insurance and safety concerns are issues they are grappling with, while angry taxi operators who feel put upon or about to be put out are also coming into play through protests and rancorous political action.

Cities, counties, states, departments of insurance and public utilities commissions are dealing with or being asked to deal with this all over the U.S.

How States Are Dealing with Ridesharing Risks

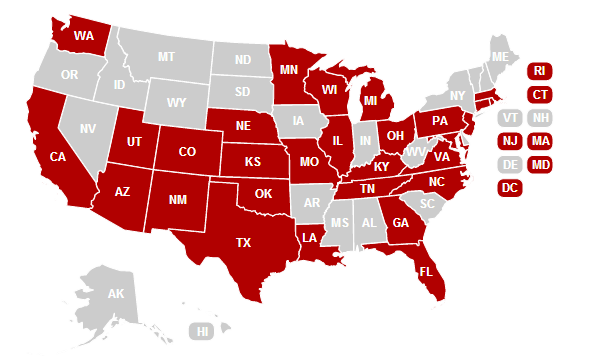

The governments of the states indicated in red are dealing in some way with the rapidly growing ridesharing trend. Click on the map to view a version of this article with interactive state-by-state details.

Information provided by the Property Casualty Insurers Association of America

Gap

A perceived gap in insurance coverage—when a TNC’s commercial insurance policy is in effect and when a driver’s personal auto policy will be expected to cover any unplanned incidents—has the insurance industry standing its ground.

The industry’s stance is that TNC drivers are providing a commercial service any time they are logged into a ridesharing smartphone app and looking for a ride. The battle has escalated to the legislative level, with PCI and other large insurers’ groups putting in regular appearances at rulemaking and legislative hearings on ridesharing throughout the nation for more than a year.

When asked, Passmore couldn’t say how much time, how many PCI staffers have worked on the ridesharing issue, or how much money was being spent.

TNC operators have agreed in several states to provide $1 million in commercial coverage for whenever a ridesharing driver has a ride. And while TNCs have offered various solutions to deal with the insurance gap, they haven’t agreed to provide the level of commercial coverage during the period insurers have pushed for.

In some cases regulators may be doing it for them.

The California Public Utilities Commission recently proposed to have its existing $1 million coverage requirement extended to all three periods of TNC service—when a smartphone app is on and when a driver is looking for a ride, when there’s a match and a driver is on the way to pick up a ride and when a driver has a ride. CPUC also is encouraging insurers to speed up the development of TNC insurance products.

California Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones has backed the CPUC recommendation, calling for the insurance burden to be put on TNCs.

A bill to more thoroughly regulate insurance requirements for ridesharing companies is successfully wending its way through California Legislature. The bill, AB 2239, would require ridesharing companies’ insurance to cover drivers from the moment they turn on their app.

However, TNCs have argued that requiring $1 million coverage for the period when drivers have their app on but no match will kill their business model, as well as scare off insurance companies currently developing TNC products.

Politics

TNCs have also accused the taxi and limo industry of stirring things up across the nation to thwart their emerging competition, as is apparent in a statement from Sidecar given at the response to a request for comment for this article.

“Established and powerful interests like the taxi industry are threatened and using their political muscle to try and stop or slow services like Sidecar, Lyft and UberX. But people want transportation choice. We hope to continue to work with leaders nationwide to create policies that strike the right balance between protecting public safety and allowing for more consumer choice in the marketplace.”

In a statement from Lyft provided by spokeswoman Paige Thelen, the company noted that despite broad publicity over the battles, there has been cooperation between TNCs and some governments and regulators.

“In April, we entered into an operating agreement with the city of Detroit for two years (or until new regulations are introduced), which is a great example of a city seeing the value in community-powered transportation and adapting to allow that model to thrive. While we have faced challenges in certain municipalities, we are hopeful that we can work together with local leaders to come to a permanent solution that puts the people first.”

Uber spokeswoman Eva Behrend said the company is optimistic about finding middle ground.

“We believe there is a solution to be found,” she said. “We think there is a solution and we do support insurance regulation.”

Colorado

In early June, Colorado became the nation’s leader as the first state to come out with a law that regulates ridesharing and addresses the insurance issue.

Gov. John Hickenlooper signed into law Senate Bill 125, which enables TNCs to operate in Colorado with limited regulation by the Colorado Public Utility Commission.

TNCs must obtain permits from the PUC and carry at least $1 million in liability insurance, and TNCs or drivers must carry primary insurance coverage during the gap between when a driver has an app on and is looking for fares but hasn’t been matched with a rider.

Those involved with the bill are optimistic it could finally set a precedent for other states to follow.

“I think it probably will be the template, if you will, that most states will look to in finding a good compromise,” said Sen. Ted Harvey, the bill’s author. “I think what we accomplished in Colorado is a very unique compromise that I think satisfies everybody’s ultimate goal to make sure there was coverage and there wasn’t any gray area.”

The bill initially included a livery exclusion stating that when a driver is not providing a ride or on their way to pick up a ride, they are to be covered under their personal auto policies.

That placed coverage in the hands of personal auto policies if a driver has the app on and is waiting to be summoned for a ride, which didn’t sit well with the insurance industry.

The argument being presented by the industry is that TNC drivers want to be near where the riders are, because TNC apps ping drivers nearest the person in need of a ride and vice versa. That entails driving to urban centers, or driving late at night—in places and at times where there are greater chances for collisions and other incidents that may trigger insurance coverage.

Driving to a crowded area can be considered a “changed behavior” for drivers, and therefore that behavior should take the liability out of the hands of personal insurers, insurers have argued.

While a version of the Colorado bill passed as was in the Assembly, an amended version that was signed by Hickenloper addressed the gap through commercial insurance.

The bill addressed some of the primary coverage questions, ensuring coverage the entire time, but at two levels of coverage, with a lower limit when a TNC driver has not yet accepted a ride, and higher limit when they have someone on board.

Uber spokeswoman Behrend said the company believes the lower limit is in line with what the company feels is a compromise.

“Colorado found a solution that adequately protects riders and drivers without ignoring the distinctions of ridesharing technology and the flexibility it affords by driver-partners and riders,” she said.

The company has a policy with carrier James River that will provide contingent coverage for a driver’s liability at the highest requirement of any state in the U.S: $50,000/individual/incident for bodily injury, $100,000 total/incident for bodily injury and $25,000/incident for property damage, according to Uber.

State-by-State

Nationwide, governments and regulators have varied broadly on their approach to TNCs.

Some states, like Connecticut and Kansas, have issued consumer alerts to drivers who work with TNCs that they may not be covered by their personal auto insurance policies while driving or to at least check with their insurer before conducting such activities.

Other areas have taken a multipronged approach.

Washington, D.C. has pending legislation that would set minimum commercial insurance requirements on TNCs, its insurance department issued a consumer alert, and the D.C. Taxi Cab Commission has proposed rules to regulate TNCs so that their commercial insurance coverage would be the primary coverage.

In Washington State, there has been action at city, county and state levels. A state bill that would have directed the Joint Transportation Committee to study TNCs and then provide a report to the legislature examining issues such as insurance coverage requirements and safety regulations has died.

However, the Seattle City Council passed an ordinance that requires commercial insurance coverage for TNCs whenever a driver is available for a ride. A rideshare coalition is preparing two ballot initiatives to challenge that regulation and limitations placed on the number of rideshare vehicles in operation.

A proposed ordinance in King County would regulate TNCs in a similar manner as taxis, but for insurance it proscribes contingent coverage.

In Illinois, the Chicago City Council passed an ordinance requiring TNCs to provide $1 million of primary noncontributory coverage. TNCs must also have $1 million in liability coverage for themselves, and $1 million for the drivers from acceptance to the end of the ride. But pending legislation could reverse the city council decision.

Cease and desist letters have been issued to ridesharing companies by cities in Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Ohio and in the Texas cities of Austin, Dallas, Houston and San Antonio.

Tip of the Iceberg

While it may seem like many of the battles have already unfolded, PCI’s Passmore believes the topic is only now just scratching the surface around the nation.

“I’ll have to say there’s more than 80 percent of this to go,” Passmore said. “At best case, at the end of this year we could have three states with laws on the books in regards to transportation networks.”

That would be Colorado, which now has a law on the books, and California and Illinois.

The states may be good models for other government bodies to follow, though there are no signs the battles will wind down. That leaves the question of whether the insurance industry is winning, or is it Uber, Lyft and Sidecar?

Passmore danced around offering an opinion on that.

“We’ve had good success so far, our message has gotten out there and our message is being listened to,” Passmore said. “Most of the stakeholders seem to understand where were coming from.”

Amy O’Connor contributed to this report.

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk

Winter Storm Fern to Cost $4B to $6.7B in Insured Losses: KCC, Verisk  Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb

Flood Risk Misconceptions Drive Underinsurance: Chubb  20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut

20,000 AI Users at Travelers Prep for Innovation 2.0; Claims Call Centers Cut  Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality

Allianz Built an AI Agent to Train Claims Professionals in Virtual Reality